Ready for some spooky science? Brace yourself, and dive into a dreadful dozen … If you dare

And remember – it's all true

1. Axolotl salamanders

All hail the "god monster." That's one nickname for the axolotl salamander of Mexico, which, due to limited resources in the one area in Mexico where they are found in the wild, has the creepy, carnivorous habit of snacking on other axolotls – which don't die. These foot-long amphibians have the death-defying ability to regenerate large portions of their limbs, tail and spinal cord -- even their heart!

Named for an Aztec god, axolotls are found only in the Xochimilco lake complex outside Mexico City. Biologists are studying these endangered creatures to see what they can teach about regenerative medicine.

2. Worm blobs

That's right – worm blobs. Aquatic blackworms that braid together – sometimes by the thousands – to move about as a creepy, crawly blob. They do this when they face environmental dangers like drought, heat or cold. Then they work together as a collective, like a single squirming brain, or a veritable Borg of worms, to head to where it's easier to survive.

Georgia Tech scientists say studying blackworm blobs could open up a big ole can of possibilities -- like novel robotic systems where soft, simple individual robots can entangle and move as a wriggly unit, accomplishing far more than they could on their own.

3. Vampire bats

Is it 5 o'clock yet? Then time for a batty, bloodthirsty happy hour – at least it is for a particular population of vampire bats in Panama, who are definitely not loners. Once these bats make friends in captivity, they coordinate in the wild, prowling together in bat packs, hooking up to sip a little full-bodied red from fresh wounds on the same cow. This is quite unlike their wild kin, who eschew hunting with a bat sidekick. Scientists at Ohio State University believe it is that initial social bonding in the roost – grooming, sharing food – that builds more interdependence and less competition and aggression later.

4. Parasitoid wasps

Remember the movie "Alien"? Guess where the inspiration for that big, bad space monster came from?

Parasitoid wasps – small bugs that lay their eggs inside the body or eggs of a host insect. Parasitoid wasps typically choose garden pests like cutworms, grubs or caterpillars. The wasp's young emerge and feed on the host, eating it alive. There are lots of species of parasitoid wasps, ranging in size from a pepper flake to 3 inches. They do not sting people, so they pose no threat to humans, but in the insect world, they are known as "tiny agents of death."

5. Tomato fruit worm

In the garden, no one can hear you scream. Not if you're a tomato plant, and a tomato fruit worm has just injected you with its saliva. Because that saliva contains an enzyme that essentially paralyzes the plant's defense mechanism – its ability to chemically cry out for help. Normally, when a tomato plant is being eaten by a caterpillar or some other insect, its leaf pores will open wide and release chemicals that attract parasitoid wasps -- those guys again -- which can lay eggs on or inside that caterpillar so the wasp's spawn can feast away, killing the caterpillar and protecting the tomato plant.

Even nearby plants can pick up the defense call. Plants can emit chemical distress signals so that neighboring plants can mount a defense, releasing protective compounds. Think about that the next time you mow your lawn. Penn State scientists say their research is the first evidence that this worm enzyme can silence a plant's chemical scream.

6. Zombie ants …

Can't get enough of "The Walking Dead" zombies? Get a load of zombie ants. The culprit in this case is not a virus, but a parasitic fungus that attaches to a rainforest carpenter ant and makes it do unnatural things.

First, it forces the ant to leave its colony in the hot canopy and descend to the humid understory where the fungi can best reproduce. There, it makes the ant bite down on the main vein of a leaf, anchoring itself in a death grip. Swiftly, the fungus grows and spreads, filling the ant's head and body, killing it. Finally, the fungus grows stalks from the ant's head to shoot spores out each night, raining down to infect even more hapless hosts.

Hungry for more? Penn State built an interactive Zombie Ant Experience sculpture wall that is installed in the university's Behrend's School of Science complex through May 2022.

7. … And zombie worms

How's this for an appetizer: rotting bones. For the deep-sea zombie worm Osedax – Latin for "bone-eater" – there's nothing yummier. Discovered in 2002 off the California coast, zombie worms feed off the dead, latching onto whatever bones happen to be lying in the cold, dark depths.

A new species was discovered in 2019 in the Gulf of Mexico. The inch-long female Osedax has a "foot" that secretes an acid that melts bone so she can tap into the marrow. And the male? Brace for it. These microscopic leeches latch onto a female by the hundreds, feeding off her body as they try to procreate. To ocean scientist Craig McClain of the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium, "they resemble snotty little flowers."

Which explains why one of the first Osedax worm discoveries is also called "mucofloris," or "mucus flower."

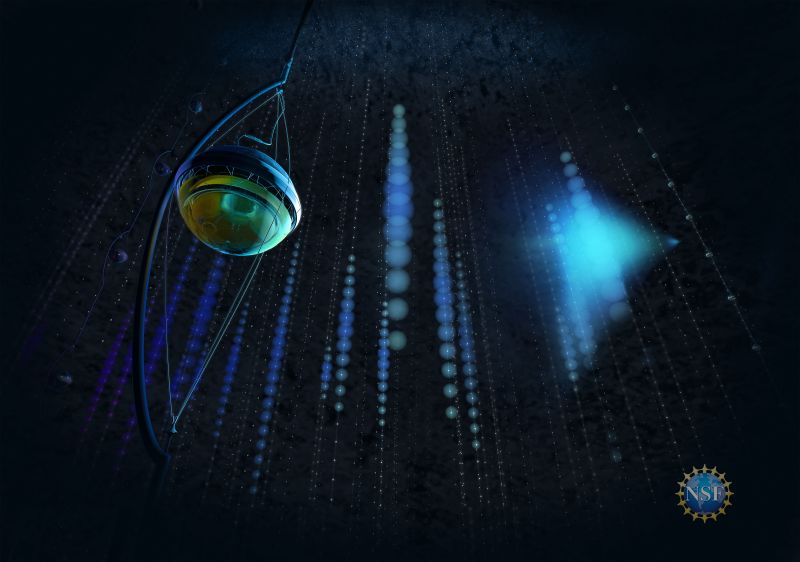

8. Ghost particles

Wait, did you feel that? And that? And a trillion times that? Just this second, trillions of subatomic neutrinos blasted right through your body at nearly the speed of light – and you never noticed a thing.

Neutrinos are called "ghost particles," because physicists thought they had no mass, weight or impact, even though they're the most common particle in the universe. A decade ago, NSF built an icebound South Pole facility, called the IceCube Neutrino Observatory, to study these elusive fundamentals of physics. In 2015 it was proven that neutrinos do have faint, spectral mass.

9. One million C.E.

Cockroaches the size of Pomeranians feasting on toxic waste and plastic. Flightless, carnivorous pigeons as big as modern-day ostriches. Aquatic whale-rats. Bats gliding on 6-foot wingspans. This is what evolutionary biologists imagine the distant future might look like as animals and plants mutate to adapt to a new Earth.

NSF is seeking research proposals to study biodiversity on a changing planet and the organismal response to climate change. The biologists expect the hardiest species will likely survive, shapeshifting as they evolve. And the weakest? Well, Darwin had an answer for that, and it's scary.

10. The first jack-o'-lanterns

Biologists plunged into the genome of two important pumpkin species, reaching back millions of years to trace the mutations that became the orange gourd that is the all-important source of pumpkin pie today. The jack-o'-lantern part is a more modern cultural mutation. Folks in Ireland and other Celtic countries would carve freaky faces into turnips and other root vegetables for Samhain – the precursor to Halloween – when they believed spirits of the dead walked the earth. They would hollow them out, stick a candle inside and use them as cheap lanterns to scare off spooks and wisps, including a specter known as Stingy Jack.

NSF research-inspired pumpkin carving stencils

11. The Invisible Man

Ever want to vanish like Harry Potter with his invisibility cloak? Well, scientists are working on it.

Mathematicians and physicists are theorizing ways to make an object invisible to thermal cameras, which pick up on an object's infrared signal. One way is to use metamaterials that can bend light and render an object invisible. Another is to use heat pumps to mimic heat transfer – making it appear as if an object was not there, or even making it appear as something else entirely.

12. 24,000 years old … and counting

Hypothermia means nothing to these Arctic rotifers – microscopic animals locked in a deep-freeze for 24,000 years, then resurrected. These icy creatures were exhumed from Siberian permafrost, thawed out, and … began reproducing. Scientists are searching for more icebound organisms capable of long-term cryptobiosis to see if they hold clues to how to cryopreserve human cells and organs.