Deep-ocean pioneers

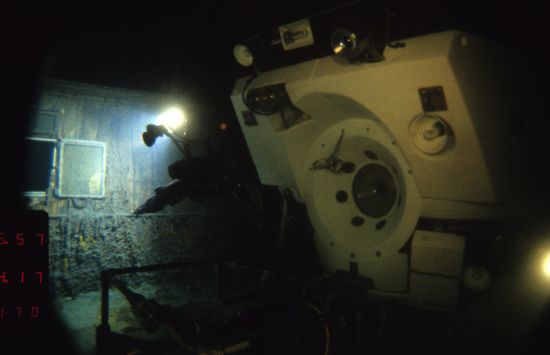

With a depth rating of 6,500 meters (4 miles), the human-occupied submersible Alvin provides unparalleled access to 99% of the world's seafloor. It allows researchers to explore, sample and map the deep ocean in person, enabling ground-breaking discoveries about the biological, chemical, physical and geological processes that shape the planet.

Alvin is one of three deep-sea vehicles in the U.S. Academic Research Fleet — including the remotely operated vehicle Jason and the autonomous underwater vehicle Sentry — operated by the National Deep Submergence Facility (NDSF) at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. NDSF is primarily funded by NSF along with the Office of Naval Research and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Some of Alvin's most famous exploits include:

Working with the U.S. Navy to locate and recover a missing hydrogen bomb off the coast of Spain in 1966.

Surveying the wreck of RMS Titanic in 1986, capturing stunning images that continue to captivate the world's imagination.

Exploring the impacts of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010 on coral communities in the Gulf of Mexico.

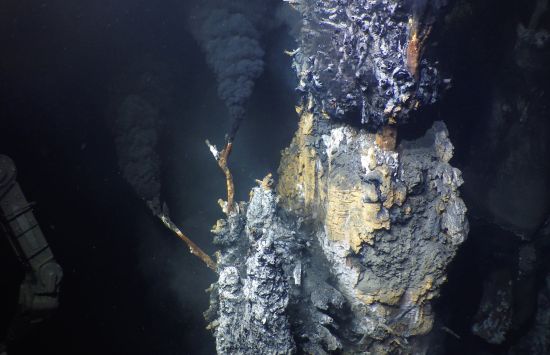

Discovering hydrothermal vents and high-temperature "black smoker" sulfide chimneys teeming with marine organisms in 1977 and 1979. Seeing life thrive under such extreme conditions revolutionized the scientific understanding of where and how life can exist on Earth and might exist beyond our planet.

Exploring the Mid-Atlantic Ridge during Project FAMOUS (French-American Mid-Ocean Undersea Study) in 1974 confirmed the theory of plate tectonics and continental drift, resulting in a paradigm shift in the geosciences.

Discovering previously unknown ancient deep-sea coral reefs within the Galapagos Marine Preserve in 2023.

Below the surface

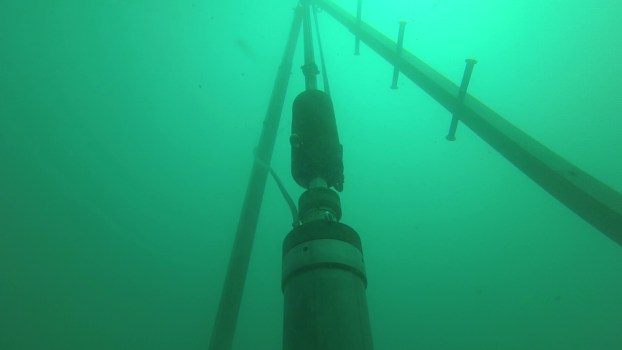

The rocks and sediments buried beneath the ocean floor hold records of millions of years of Earth's climatic, biological, chemical and geological history. By drilling and collecting core samples from the seafloor, researchers can study seafloor compositions and ages to answer fundamental questions about Earth's climate history and deep-ocean environment.

NSF has supported scientific ocean drilling since the 1950s, providing continuous funding for the Deep-Sea Drilling Project and its successors — the Ocean Drilling Program, the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program and the International Ocean Discovery Program.

Scientific ocean drilling has yielded numerous significant discovers, such as:

- Evidence of seafloor spreading, validating the theory of plate tectonics and continental drift.

- Critical insights into the role of fluid flow within the ocean crust, from mid-ocean ridges to deep-sea trenches.

- Existence of a vibrant microbial ecosystem beneath the seafloor at depths far deeper than researchers ever predicted life could exist.

- Reconstruction of paleoclimate records through various climate proxies, revealing changes in the Earth’s climate over the past 150 million years.

- High-resolution records of sea level change over the last 10 to 15 thousand years following the Last Glacial Maximum.

- Recovery of the most complete marine records of the Cretaceous/Paleogene mass extinction event 66.05 million years ago.

- Recovery of the first long section of rock from the Earth's mantle.

Age of discovery

NSF is actively exploring new technology that will enable the next phase of oceanographic research in complex ocean, seafloor and sub-seafloor environments, including the Great Lakes and remote polar regions.

Credit: Ivo Gallmetzer, CC BY

Credit: Sarah Kachovich/IODP JRSO