Bacteria May Thrive in Antarctica's Buried Lake Vostok

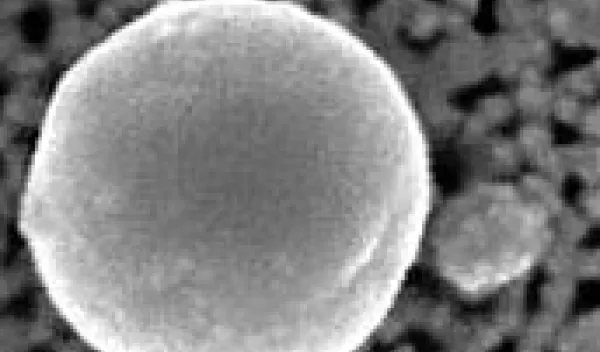

Two separate investigations of ice drilled at Lake Vostok, a suspected body of water thousands of meters below the ice sheet in the Antarctic interior, indicate that a potentially large and diverse population of bacteria may call the lake home. If so, this bacteria answers an intriguing scientific question about whether an extremely cold, dark environment that is cut off from a ready supply of nutrients can support life.

Two NSF-funded research teams, led by David M. Karl from the University of Hawaii and John C. Priscu of Montana State University, examined fragments of ice taken from roughly 3,600 meters (11,700 feet) below the surface -- about 120 meters (393 feet) above the interface of ice and suspected water. Both teams found bacteria in "accreted" ice, or ice believed to be refrozen lake water.

DNA analysis by Priscu's team indicates that although the bacteria have been isolated for millions of years, they are biologically similar to known organisms. "Our research shows us that the microbial world has few limits on our planet," Priscu said. He added that Lake Vostok, roughly the size of Lake Ontario in North America, "is one of the last unexplored oases for life" on Earth.

The teams also concluded that microbes could thrive in other, similarly hostile, places in the solar system. Lake Vostok is thought to be an analog to Europa, a frozen moon of Jupiter. Priscu notes in his paper that the Galileo spacecraft found evidence that liquid water exists under an icy crust on the Jovian moon. "Similar to ice above Lake Vostok, this ice may retain evidence for any life, if present, in the Europan ocean," he wrote.

Evidence from radar mapping and other sources indicates that, under several thousand meters of ice, Lake Vostok may be filled with liquid water, possibly warmed by the pressure of the ice above or by thermal features below.

The Russian scientific outpost Vostok Station, which once recorded the lowest temperature on earth (-126.9 degrees Fahrenheit/-89.9 degrees celsius), is located on the ice above the lake. As part of a joint U.S., French and Russian research project, Russian teams have drilled down into the ice covering the lake, producing the world's deepest ice core. Drilling was deliberately stopped to prevent introducing materials that would contaminate the water.

At least one outstanding question remains about the discovery: whether the ice in which the bacteria were found is sufficiently similar to the water in the lake to allow scientists to conclude that a similar population -- or an even larger, more diverse one -- might thrive in the suspected liquid water.

Delegates from several nations, including a U.S. delegation sponsored by NSF, are continuing to discuss how to explore the suspected lake without contaminating it. "We don't know what's in Lake Vostok, and we may never know, if we don't get the contamination issues solved," Karl said.

While the teams' 1999 findings, reported in Science, may prove the existence of life in the lake, "there are other, compelling reasons to go into the lake," Karl concluded. Ice cores have helped scientists assemble a climate record stretching back more than 400,000 years. Sediment samples from the bottom of Lake Vostok could extend that record to cover millions of years.

-- Peter West