Can Marcellus Shale Gas Development and Healthy Waterways Sustainably Coexist?

Find related stories on NSF's Environmental Research and Education (ERE) programs at this link and NSF's Critical Zone Observatories (CZOs) at this link.

Amity, Pennsylvania. Epicenter of the natural gas-containing geological formation known as the Marcellus Shale.

Amity lies in Washington County near Anawanna, Pennsylvania. Once, Native Americans lived there. They named it Anawanna, or "the path of the water," in recognition of its many rivers and streams.

Today the Native American Anawanna is but a whisper in tales of the past, but the path of the water for which it's named is making headlines.

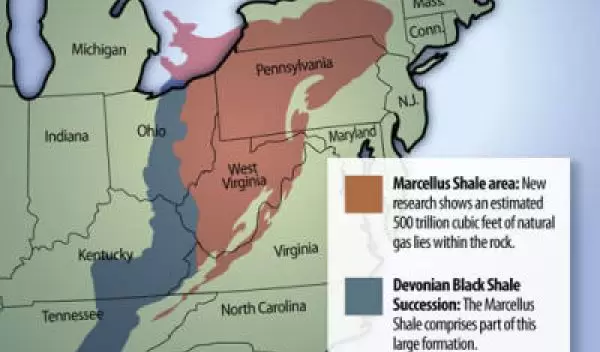

The Marcellus Shale Formation underlies some 95,000 square miles of land, from upstate New York in the north to Virginia in the south to Ohio in the west.

The bull's-eye, however, is under Pennsylvania in places like Amity. There the gas-bearing thickness of the shale reaches 350 feet; it thins to less than 50 feet in other areas.

The Marcellus Shale gas reservoir may contain nearly 500 trillion cubic feet of technically-recoverable gas. At current use rates, that volume could meet the U.S. demand for natural gas for more than 20 years.

The shale's proximity to the heavily populated mid-Atlantic and Northeast makes its development economically advantageous. Already, more than 4,000 shale gas wells have been drilled in Pennsylvania.

But the Marcellus Shale has a bête noire. With such rapid development, gas exploitation is creating environmental challenges for Pennsylvania--and beyond.

Retrieving the Marcellus Shale's gas requires a process known as hydraulic fracturing, hydrofracking or simply fracking.

Fracking involves the use of large quantities of water, three to eight million gallons per well, mixed with additives, to break down the rocks and free up the gas. Some 10 to as much as 40 percent of this fluid returns to the surface as "flowback water" as the gas flows into a wellhead.

Once a well is in production and connected to a pipeline, it generates what's known as produced water. "Flowback and produced water," says Susan Brantley, a geoscientist at Penn State University, "contain fluid that was injected from surface reservoirs--and 'formation water' that was in the shale before drilling."

Enter the bête noire.

These flowback fluids carry high concentrations of salts, and of metals, radionuclides and methane. "Such chemicals," says Brantley, "can affect surface and groundwater quality if released to the environment without adequate treatment."

The rapid pace of Marcellus Shale drilling has outstripped Pennsylvania's ability to document pre-drilling water quality, even with some 580 organizations focused on monitoring the state's watersheds. More than 300 are community-based groups that take part in volunteer stream monitoring.

Pennsylvania has more miles of stream per unit land area than any other state in the United States. "It's overwhelming to keep track of," says Brantley. "These community organizations have identified a need for scientific and technical assistance to carry out accurate stream assessments."

Working through the National Science Foundation's (NSF) Susquehanna Shale Hills Critical Zone Observatory (CZO), one of six such observatories in the continental U.S. and Puerto Rico, Brantley studies the "critical zone" where water, atmosphere, ecosystems and soils interact.

Now, with a grant from NSF's Science, Engineering and Education for Sustainability (SEES) Research Coordination Networks (RCN) activity, Brantley is developing a Marcellus Shale Research Network.

The network will identify groups in Pennsylvania that are collecting water data in the Marcellus Shale region; create links among these organizations to meld the resulting data; and organize a water database through the NSF-funded Consortium of Universities for the Advancement of Hydrologic Sciences.

The database will be used to establish background concentrations of chemicals in streams and rivers, and ultimately to assess changes throughout the Marcellus Shale area.

The results, Brantley hopes, will help community groups evaluate hydrogeochemical data. The network will use geographic information systems that incorporate population and economic data to evaluate the potential for public health risks.

"An outcome of the NSF investment in the Susquehanna Shale Hills Critical Zone Observatory has been a better interpretation of the chemistry and flow of groundwater in shale," says Enriqueta Barrera, program director in NSF's Division of Earth Sciences, which funds the CZOs.

"The SEES-RCN project will use this information in assembling data collected by watershed associations, government agencies, and water scientists to further knowledge on the effect of hydrofracking on groundwater properties."

The Marcellus Shale RCN, says Brantley, "is designed to act as an 'honest broker' that collates datasets and teaches ways of synthesizing the data into useful knowledge. The approach stresses that volunteer data acts as a 'canary in a coal mine' to inform agencies about when and where they need to intensify water quality monitoring."

Of particular concern are concentrations of salts such as barium and strontium, high in some discharges as a result of the mixing of gas drilling fluids with naturally-occurring barium-strontium-containing waters.

"Barium can cause gastrointestinal problems and muscular weakness," says Brantley, "when people are exposed to it at levels above the EPA drinking water standards, even for relatively short periods of time.

"Animals [such as cows, pigs, sheep] that drink barium-laced waters over longer periods sustain damage to kidneys and have decreases in body weight, and may die of the effects."

The waterways of Pennsylvania have recorded many of the important human activities in the history of the United States, Brantley says. "It's expected that they will record the development of the Marcellus Shale gas as well."

The rise and fall of coal mining is found in concentrations of dissolved sulfates in the state's rivers. Pennsylvania's air, water and soils retain the signature of the steel industry and of coal-burning over the last century in their low-level manganese contamination.

Documenting the effects of shale gas extraction, says Brantley, requires extensive water sampling and a database of long-term records.

In the past, monitoring sometimes has not begun until after effects were noticed. But times are changing. "In the future," says Brantley, "many monitoring networks of all kinds will need to include citizen scientists to keep costs down, and research scientists will need to learn to use such networks to the best outcome."

Can we have natural gas development and clean waterways?

The Marcellus Shale Research Network will provide much-needed answers, says Barrera. "Successfully developing new energy resources while maintaining healthy ecosystems," she says, "is the very heart of sustainability."