Climate change, urbanization drive declines in LA's birds

Climate change isn't the only threat facing California's birds. Over the course of the 20th century, urban sprawl and agricultural development have dramatically changed the landscape of the state, forcing many native species to adapt to new and unfamiliar habitats.

In a U.S. National Science Foundation-supported study, biologists at the University of California, Berkeley, used current and historical bird surveys to reveal how land use change has amplified — and in some cases mitigated — the impacts of climate change on bird populations in Los Angeles and the Central Valley.

"This is a beautifully complex study," said Doug Levey, a program director in NSF's Division of Environmental Biology. "It's rare for ecologists to have such detailed records from 100 years ago, allowing them to detect exactly how birds are reacting to a changing world."

The study found that urbanization and much hotter and drier conditions in L.A. have driven declines in more than one-third of bird species in the region over the past century. Meanwhile, agricultural development and a warmer and slightly wetter climate in the Central Valley have had more mixed impacts on biodiversity.

"It's pretty common in studies of the impact of climate change on biodiversity to only model the effects of climate and not consider the effects of land use change," said study senior author Steven Beissinger of UC Berkeley. "But we're finding that the individual responses of different bird species to these threats are likely to promote unpredictable changes that complicate forecasts of extinction risk."

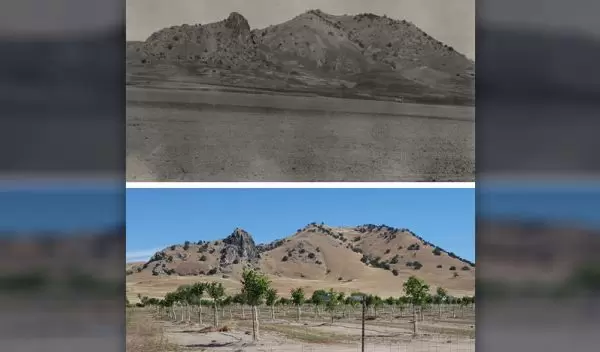

The study, published in the journal Science Advances, presents the latest results from UC Berkeley's Grinnell Resurvey Project, an effort to revisit and document birds and small mammals at sites first surveyed a century ago by UC Berkeley professor Joseph Grinnell.

The researchers resurveyed birds at 71 sites in L.A. and the Central Valley. They then used their findings — along with current and historical data on land use, average temperature, and rainfall — to analyze how shifts in the climate and landscape may have contributed to changes in bird populations.

In L.A., they found that 40% of bird species were present at fewer sites today than they were 100 years ago, while only 10% were present at more sites. In the Central Valley, the proportion of species that experienced a decline (23%) only slightly outnumbered the proportion that increased (16%). In many cases, opposing responses to climate and land use change by bird species — where one threat caused a species to increase while another caused the same species to decline — moderated the impacts of each threat alone.

The decline in bird species in L.A. over the past century is similar to the bird community collapse the research team documented in national parks in the Mojave Desert over the past 100 years, which was linked to heat stress from climate change.

"The Central Valley had less change, in general — there were winners and losers," Beissinger said. "Whereas in L.A., we saw mostly losers."