Colorado high peaks losing glaciers as climate warms

Find related stories on NSF's Long-Term Ecological Research Program at this link.

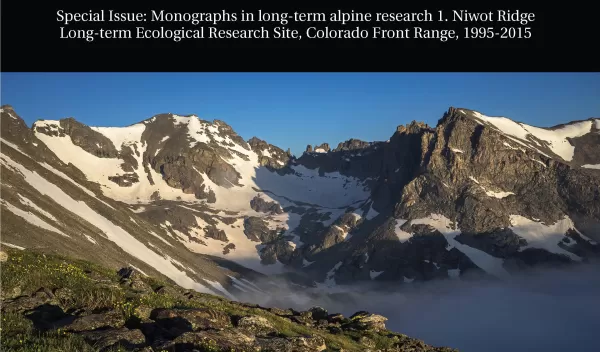

Melting of ice on Niwot Ridge and the adjacent Green Lakes Valley in the high mountains west of Boulder, Colorado, is likely to progress as climate continues to warm, scientists have found.

They report their results in a special issue of the journal Plant Ecology and Diversity.

The study area is in the National Science Foundation (NSF) Niwot Ridge Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) site. It encompasses thousands of acres of alpine tundra, subalpine forest, talus slopes, glacial lakes and wetlands at the top of the Continental Divide in the Rocky Mountains.

The site includes Green Lakes Valley and the University of Colorado (CU) Boulder's Mountain Research Station.

Changing cryosphere

The researchers looked at changes in the cryosphere -- places that are frozen for at least one month of the year -- at the Niwot Ridge site, going back to the 1960s.

The decline of ice is linked with rising temperatures each summer and autumn in recent years, said ecologist Mark Williams of CU Boulder's Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research.

In addition to Williams, co-authors of a paper on the changing cryosphere published in the special issue include Nel Caine of CU Boulder, Matthew Leopold of the University of West Australia, and Gabriel Lewis and David Dethier of Williams College.

"This study reveals declines in ice -- glaciers, permafrost, subsurface ice, lake ice -- in the Niwot Ridge area over the past 30 years," said Saran Twombly, LTER program director in NSF's Division of Environmental Biology, which funded the research. "Long-term research at Niwot Ridge offers a rare opportunity to document the continuous, progressive effects of climate change on high alpine ecosystems, from ice to nutrients to plant and animal communities."

The ice melt is especially evident on the Arikaree Glacier -- the only glacier on Niwot Ridge -- which has been thinning by about 3 feet per year for the last 15 years.

"Things don’t look good up there," said Williams. "While there was no significant change in the volume of the Arikaree Glacier from 1955 to 2000, severe drought in Colorado beginning in 2000 caused it to thin considerably. Even after heavy snows in 2011 and again in 2014, we believe the glacier is on course to disappear in about 20 years."

Waning glaciers

In addition to the changes occurring on Arikaree Glacier, scientists have seen decreases in ice in three rock glaciers (large mounds of ice, dirt and rock) as well as in subsurface areas of permafrost -- frozen soil containing ice crystals.

The team used several methods to measure surface and subsurface ice on Niwot Ridge: ground-penetrating radar, which measures ice and snow thickness; resistivity, which records the conductivity of electrical signals through ice; and seismometers to track signals bounced through subsurface ice.

"We found that a combination of all three methods provided the best picture of changing snow and ice conditions on Niwot Ridge," Williams said.

The researchers also discovered increased discharges of water from Green Lakes Valley in late summer and fall after the annual snowpack has melted.

The increases appear to be due to higher summer temperatures melting "fossil" ice present for centuries or millennia in glaciers, rock glaciers, permafrost and other subsurface ice.

"We are taking the capital out of our hydrological bank account and melting that stored ice," Williams said. "While some may think this late summer water discharge is the new normal, it is really a limited resource that will eventually disappear."

Scientists have been gathering information on snow, ice, and plant and animal abundance and diversity on Niwot Ridge since the 1940s. The two highest climate stations on Niwot Ridge, one at 10,025 feet and the other at 12,300 feet, have been collecting data continuously since 1952.

High mountain ecosystem

Niwot Ridge has seen a significant increase in alpine shrubs above treeline in recent decades, said Williams.

At one research site known as the Saddle, about 11,600 feet high and 3.5 miles from the Continental Divide, the ecosystem has gone from all tundra grasses and no shrubs in the early 1990s to about 40 percent shrubs today.

"Places that once harbored magnificent wildflowers are being replaced by shrubs, particularly willows," he said. "The areas dominated by shrubs are increasing because of a positive feedback – patches of these shrubs act as snow fences, causing the accumulation of more water and nutrients and the growth of more shrubs."

One nutrient, nitrogen -- produced primarily by vehicle emissions and agricultural and industrial operations on the Front Range and elsewhere in the West -- is being swept into the atmosphere and deposited on the tundra in increasing amounts, said Williams.

Nitrogen deposition is also an issue in nearby Rocky Mountain National Park.

For glaciers like Arikaree and the plants their meltwaters sustain, the time left may be counted in years, not centuries nor millennia.