Communicating a hurricane's real risks

A hurricane is heading toward the coast. Weather forecasters predict strong winds, massive waves and intense rainfall. But what does that mean for you? Will your neighborhood be flooded? Should you evacuate?

A surprising and little known fact: More than half of those who die during hurricanes perish from drowning.

"If you look at the history of deaths in the U.S. from hurricanes, the vast majority of people are not dying from winds," said Jamie Rhome, storm surge specialist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) National Hurricane Center. "Most deaths are attributable to water and the biggest water hazard is storm surge."

And yet, the familiar terms used for measuring hurricanes--the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale--refer primarily to wind-speeds.

For the first time this year, scientists began communicating warnings that included storm surge. A composite measure that combines weather predictions with oceanographic data and geographic information about a given area to determine where and how high waves may reach, storm surge is the basis for most evacuation decisions by authorities. Well understood by scientists, it has long been a puzzle to the public and even to forecasters.

"As a nation, we're just not prepared or knowledgeable about storm surge risks and the problem is going to get worse and worse as sea level rises," Rhome said. "It's like we're on a collision course with the ocean."

There are lots of research questions inherent in accurately forecasting storm surge. But for Jeff Lazo, director of the Societal Impacts Program at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), the most important question is: How do you communicate storm surge risk to the public in a way that they'll understand, take seriously and respond appropriately to?

With support from NOAA and the National Science Foundation (NSF), Lazo and a team of interdisciplinary experts examined the entire creation, use, understanding and value of weather information and warnings from a variety of viewpoints.

"Everything from how does the forecaster understand the models? How do they communicate it? How do the media pick it up?" Lazo said. "We've done work with broadcasters, emergency managers and members of the general public--everybody who uses weather information. There's a social science aspect to understanding how this information is used and how it can save lives."

Collaborating over several years with Jamie Rhome and Jesse Feyen from NOAA and Betty Morrow from SocResearch Miami, the team surveyed citizens in numerous coastal areas to gather perspectives on how storm surge risk is communicated and to what messages people respond most.

Their results, published in the January 2015 edition of the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society and the March/April 2014 issue of the Journal of Emergency Management, helped guide the development of the National Hurricane Center's newest weather product: a storm surge warning system that is currently in the public testing phase.

Gauging the status quo

To begin, the research team surveyed the public on their knowledge about their storm surge risk.

"We started from the basics: do people understand storm surge now? And the answer was no," Rhome said. "The amount of people who just didn't understand that they were vulnerable to storm surge, or even what storm surge was, was shocking."

The researchers then asked individuals what they thought about the previous weather service product that represents storm surge--a text-based announcement written in technical jargon--and determined that it wasn't meeting the needs of the public.

To provide clearer communication to the public, the National Hurricane Center would need to change the words that it used in its text messages. The developers wanted to put in wording about storm surge depth that required calculations and some knowledge of the tides to translate into tangible terms. For instance, Lazo et al.'s research suggested using "height above ground" instead of "storm surge depth," based on how people generally interpreted each phrase.

"The way we used to do storm surge required you to be a storm surge expert or have significant experience with hurricanes to decipher the message," Rhome acknowledged. "We've gone from a physical science-oriented approach--very complex and precise, with precise words--to something that the average person could understand."

Working with Ann Bostrom from the University of Washington and Rebecca Morss, Julie Demuth and Heather Lazarus from NCAR, the team uncovered other potentially useful findings, too. For instance, they found that people who are highly individualistic were less likely to evacuate under an evacuation order than those who are egalitarian. They also found that the biggest factor in deciding to evacuate was the motivation to protect one's family.

"As opposed to saying: 'This is a Category 3 storm with 125 mile per hour winds,' which doesn't mean anything to anybody, maybe focusing communication on keeping you and your family safe would work better," Lazo said.

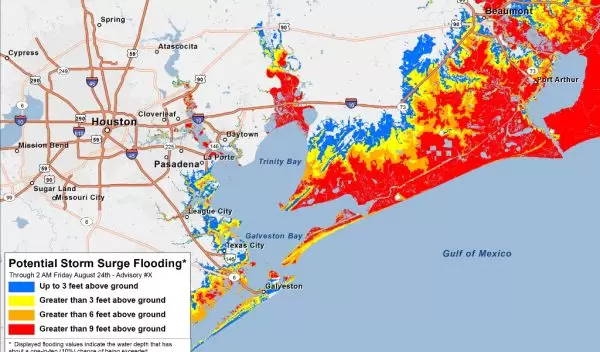

Lazo and his team also did preliminary work on the graphics the National Hurricane Center would ultimately develop to accompany their announcements.

"We went out and said: 'If you got this warning, what would it mean to you?' Then we found the wording, colors and maps that worked better," Lazo said.

Testing a new storm surge communication system

The results of the team's research are reflected in the new graphical warning system that NOAA launched in experimental mode last summer to widespread praise.

The Potential Storm Surge Flooding Map, with its bright, clean, eye-catching graphics and plain English descriptions of weather conditions, is a world away from the previous communication techniques.

The product is available on the web in real time, using real data and real storms.

In 2015, the experimental "Storm Surge Watch/Warning" graphic will be introduced, but will not yet be distributed via the formal storm warning dissemination systems. Updated versions of the new dedicated storm surge warning system will come online in phases between 2015 and 2017.

"As seen in this project, National Science Foundation support for scientific research that brings together social scientists and meteorologists can have a great impact on our nation's resiliency," said Robert O'Connor, a program officer in Directorate for Social, Behavioral and Economic Sciences at NSF. "The work has helped social scientists understand how people treat official warnings in a culture of widespread distrust while providing new knowledge useful to practitioners."

While weather warning debates can often get caught up in the minutiae of higher-resolution models and degrees of uncertainty, sometimes the best way to increase safety is to determine what messages resonate with people and to provide information in formats they understand.

"The social sciences have a great potential value to add to the meteorological community," Lazo said. "For every dollar that we put into improving the forecasts, we need to make sure we're investing in making sure the forecasts are communicated, used and understood as opposed to just doing better physical science. We need to do better with the whole process for society to benefit."