Cooking Up Clean Air in Africa

Find related stories on NSF's Environmental Research and Education (ERE) programs at this link.

Where there's smoke, there's disease?

They're little more than a pile of burning sticks with a stewpot atop them.

But these open fires or basic cookstoves have been linked to the premature deaths of 4 million people annually, many of them young children.

Three billion people around the world rely on wood, charcoal, agricultural waste, animal dung and coal for household cooking needs. They often burn these fuels inside their homes in poorly ventilated stoves or in open fires.

The resulting miasma exposes families to air pollution levels as much as 50 times greater than World Health Organization guidelines for clean air, setting the stage for heart and lung disease.

Household air pollution can also lead to pneumonia in children and low birth weight in infants.

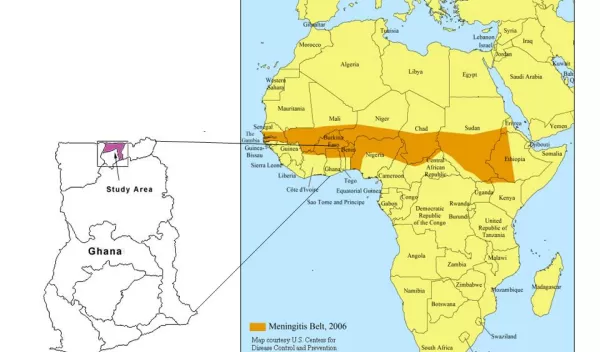

Now, researchers believe the smoke may be a contributing factor in bacterial meningitis outbreaks in countries such as Ghana, whose northern region is located in Africa's "meningitis belt."

An estimated 300 million people live in the meningitis belt, which includes part or all of The Gambia, Senegal, Mali, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Niger, Nigeria, Cameroon, Chad, Central African Republic, Sudan, South Sudan, Uganda, Kenya, Ethiopia and Eritrea.

Those exposed to indoor air pollution from cooking over open flames are nine times more likely to contract meningitis, studies show.

Meningitis, a potentially deadly disease, is an inflammation of the membranes covering the brain and spinal cord. Most cases are caused by a viral infection, but bacterial and fungal infections are also culprits. Bacterial meningitis is the most dangerous form.

Outbreaks usually happen in the dry, dusty season, and end with the onset of the seasonal rains.

The dust and dryness may irritate sensitive human membranes, making victims vulnerable to infection. Cooking smoke may play a similar role, increasing susceptibility to meningitis.

"Smoke from cooking practices may irritate the lining of the mucosa, allowing bacteria to become invasive," says Christine Wiedinmyer of the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder, Colo.

Links among cookstoves, air pollution and human health

Wiedinmyer and colleagues have been awarded a grant from the National Science Foundation's (NSF) Coupled Natural and Human Systems (CNH) Program to study the effects of cookstoves in northern Ghana.

CNH is part of NSF's Science, Engineering and Education for Sustainability (SEES) investment, and is supported by NSF's Directorates for Geosciences, Biological Sciences, and Social, Behavioral & Economic Sciences.

The study is breaking new ground by bringing together atmospheric scientists, engineers, statisticians and social scientists.

Researchers are analyzing the effects of smoke from traditional cooking methods on households, villages and entire regions--and whether introducing more modern cookstoves will help.

They hope their findings will reach across the African Sahel, the semi-arid zone between the Sahara Desert in the north and the savannas of Sudan in the south.

Integrating the physical, social and health sciences

"The adoption of more efficient cookstoves could lead to significant improvements in public health and environmental quality," says Sarah Ruth, a CNH program director at NSF, "but research has usually focused on the effects on individual households, local air quality, or the weather and climate system.

"By integrating the physical, social and health sciences, these scientists are providing a more complete analysis of the costs and benefits of improved cookstoves."

An overview of the research was presented at NSF in November 2012, as part of a forum featuring NCAR research.

The results will provide critical information to policymakers and health officials in countries where open-fire cooking or inefficient cooking practices are common.

"When you visit remote villages during the dry season," says Wiedinmyer, an atmospheric chemist, "there's a lot of smoke in the air from cooking and other burning practices.

"We need to understand how these pollutants are affecting public health and regional air quality and, in the bigger picture, climate."

To find out, the scientists are using a combination of local and regional air quality measurements; new instruments with specialized smartphone applications that are more mobile than traditional air quality sensors; and computer models of weather, air quality and climate.

"The project involves exploring new technologies to improve human health and well-being while also improving environmental quality," says Tom Baerwald, an NSF program director for CNH.

"By looking at this problem from social, cultural, economic, health and atmospheric science perspectives, these researchers are developing a framework that will help people in many other regions."

Scientists and local communities working together

The scientists are surveying villagers to obtain their views on possible connections between open-fire cooking and disease--and whether community members are willing to adopt different cooking methods.

Cooking fires are a major source of particulates, and of carbon monoxide and other gases that lead to smog.

The fires also emit heat-trapping gases such as carbon dioxide that, when mixed into the global atmosphere, can affect climate.

Widespread use of more efficient, or "clean," cookstoves--which can produce less smoke than open fires--may lower these toxic emissions.

"Newer, more efficient cookstoves could reduce disease and result in improved regional air quality," Wiedinmyer says.

To find out, the scientists are introducing upgraded cookstoves into randomly selected households across the Kassena-Nankana District of Ghana.

In addition to determining whether the clean cookstoves improve air quality and human health, the researchers are exploring the social and economic factors that encourage or discourage such cookstove use.

It takes a village

They're asking villagers for help.

"Community members will assist with measuring air quality and reporting disease," says social scientist Katie Dickinson of NCAR.

Dickinson, Wiedinmyer and others are working with townspeople to develop scenarios in which realistic changes in cooking practices interact with climate processes to improve air quality and reduce respiratory illness and bacterial meningitis.

"We hope this project will alleviate a major health problem," says Mary Hayden, a medical anthropologist at NCAR, "one that extends across the entire Sahel."