Cool Cat in a Hot Zone

Find related stories on the NSF, National Institutes of Health and U.S. Department of Agriculture's Ecology and Evolution of Infectious Diseases (EEID) program at this link.

What do Ventura County, Calif., and the Front Range of Colorado's Rocky Mountains have in common?

Ventura, which encompasses the city of Los Angeles, has a Mediterranean climate and habitat; the Front Range surrounding Denver is cooler, drier and is lined with tall conifers instead of low, dense shrubs.

Both, however, have people. Lots of them.

But it's what else they have in common that tells the real tale of these urban areas.

Alley cat of the wild

It's on the move from three hours before sunset until midnight, and again before dawn ‘til three hours after sunrise. Each night it roams two to seven miles, mostly along the same route.

Like humans, it visits known locales along the way. In this case, though, those places are a hollow log or two, a brush pile or thicket and the underside of a rock ledge.

It also shares something far more personal with the people it quietly lives alongside: gastrointestinal diseases.

It's a bobcat, and we gave it our afflictions rather than the other way around, say scientists Sue VandeWoude, Kevin Crooks, Mike Lappin and Andrea Scorza of Colorado State University at Fort Collins; Scott Carver of the University of Tasmania; Sarah Bevins of the U.S. Department of Agriculture and Seth Riley of the U.S. National Park Service.

The researchers published results of their study of the parasites bobcats and humans share in a recent issue of the Journal of Clinical Microbiology.

Their work is funded by the joint National Science Foundation (NSF) and National Institutes of Health (NIH) Ecology and Evolution of Infectious Diseases (EEID) Program.

"The growing interaction of humans and wildlife means that we now share our diseases with each other at an ever-increasing rate," says Sam Scheiner, EEID program officer at NSF.

NSF's EEID program is funded by the agency's Division of Environmental Biology and Division of Ocean Sciences.

"This study demonstrates that we and our wild animal neighbors," says Scheiner, "are closely interconnected in ways that affect the health of us all."

The spillover effect

Pathogen spillover, as it's known, is a major source of disease in humans and in wildlife.

Indeed, bobcats are more likely to pick up parasites such as Giardia when the cats are closer to urban areas, VandeWoude and colleagues found.

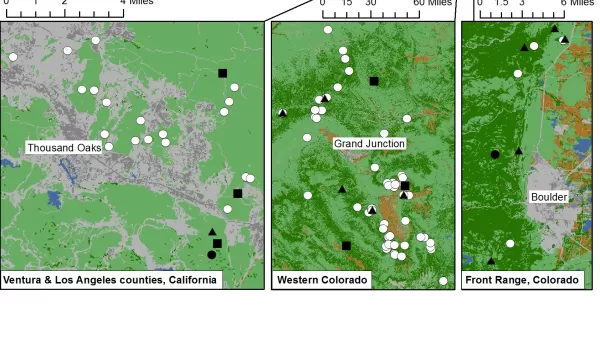

They collected bobcat fecal samples in Ventura County and on the Front Range and tested them for Toxoplasma gondii, Giardia duodenalis and Cryptosporidium spp. All are disease-causing parasites found in wildlife and in people. Contact with the latter two results in diarrhea and other gastrointestinal upsets.

The scientists compared samples from bobcats in the two urban areas with those from rural areas of Colorado.

The findings show that city bobcats are more likely than country bobcats to carry parasites.

"Bobcats are exposed to and shed more zoonotic [i.e., may be transmitted between species] parasites near human-occupied landscapes," says Crooks.

But how did the cats, which are smaller relatives of threatened Canadian lynx, acquire the parasites?

"They were probably exposed to the water supply around cities," says VandeWoude. Parasites all-too-often lurk there.

Cryptosporidium parvum and Giardia duodenalis account for the majority of waterborne disease outbreaks in humans, with hundreds of thousands of cases in the United States alone every year.

Studies have long suggested that wild cats such as bobcats might contribute to a spillover of pathogens to humans, and vice-versa. But with the cats' secretive natures, few researchers have been able to draw conclusions about wild cats' "shedding" of disease-causing microbes. This study is the first.

A disease continuum

Bobcats are widespread in North America. They traverse a continuum of natural to urbanized habitats, often living side-by-side with humans, domestic animals and other urban-adapted wildlife species.

"Along these boundaries," says VandeWoude, "close living quarters make it easy for one species to transmit diseases to another."

In a city or suburb, pathogens travel from human to bobcat, and bobcat to human, the scientists found, almost as fast as a virus that infects one human family member runs through an entire household.

Whether that household lives in a two-story A-frame or a two-story log pile, there's not much difference, it turns out, in the spread of diseases.

It must be something in the water

It's when everyone heads for the water that things really begin to ramp up.

One group of bobcats in Ventura County, says Carver, the paper's lead author, left its calling card in the Malibu Creek watershed: Cryptosporidium and Giardia. Malibu Creek's environs are heavily populated by bobcats--and humans.

"Our results suggest that humans transmitted these pathogens to bobcats," says Carver, "likely through contaminated water or other environmental sources."

At the time of the study, there was no evidence that bobcats carrying the parasites were ill. But for these cool cats that roam along our streets and through our backyards, life in the ‘burbs can be a chancy existence. Simply crossing an urban stream may be walking through a hot zone.

For bobcats. And for humans.