Creative Minds Mingle: Robotics at the Junction of Art and Engineering

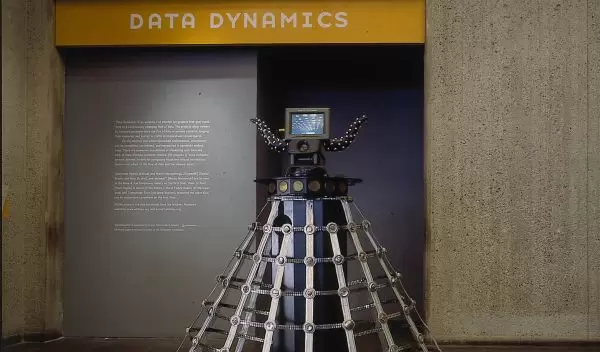

In 2001, visitors to the "Data Dynamics" exhibition at New York's Whitney Museum of American Art unwittingly joined a social experiment.

For three months that spring, a child-sized robot roamed the museum lobby and mingled with visitors as part of a show by local artist Adrianne Wortzel and a team of students from the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art. The students--art, engineering and architecture undergraduates--were participants in a National Science Foundation- (NSF) funded robotics lab course taught by Wortzel and Cooper Union engineering professor Carl Weiman.

The exhibit was a concrete product of a project aimed at the intangible--namely, the bridging of traditional academic disciplines by creative minds.

At times during the exhibit's run at the Whitney, the robot spouted prerecorded speeches and moved about the room autonomously. But most of the time, in fact, it was under the control of anonymous Internet users around the world.

By logging onto Wortzel's Web site, anyone could gain control of the robot for a minute at a time. Whatever text the person typed, it would speak. Whatever direction the person indicated, it would follow. By navigating the robot around the museum and watching streaming video on the Web site, visitors saw through the robot's "eyes"--two video cameras mounted on its head--and also through six surveillance cameras mounted on the ceiling.

Some unsuspecting patrons found themselves trailed across the museum lobby or into the elevator. Others were greeted with polite conversation or nonsensical chatter. At the end of each day, the robot rolled to a window overlooking Madison Avenue, where it remained, muttering softly, until morning.

Meet Kiru, the protagonist of Wortzel's "Camouflage Town"--the name for the imaginary world the robot inhabited. Alternately described by Wortzel as a "cultural curmudgeon" or "master of juxtapositions," Kiru was born as an off-the-shelf Peoplebot made by Activemedia Robotics, a company that designs robots to interface with people.

Wortzel, who holds professorships at Cooper Union and the City University of New York, purchased Kiru with a grant from NSF and support from the NSF-funded Gateway Engineering Education Coalition at Cooper Union.

Trained as a painter, Wortzel dabbled in photography and film before she went to graduate school to study computer arts. Graduate school was a practical decision, Wortzel told an interviewer for the art organization Wigged Productions. "I thought of it just in the same way and with the same enthusiasm I feel when I consider that death is at the end of life."

But it was during graduate school that she discovered the medium that would be the vehicle for many of her future pursuits: the Internet. "Conceptually, anything was possible," Wortzel says. "You could connect to real data or fake data, there are all these nodes that interconnect in unpredictable ways, and everything is available for interpretation."

Long fascinated by the uses of "avatars"--the virtual personas adopted by Internet gamers--Wortzel wondered what would happen if web users could guide a character through the real world instead. She embarked upon the Kiru project with that goal in mind.

"I had spent a lot of time in virtual communities," says Wortzel, "and I thought, 'If I'm going to have avatars, I'd like to make them clunky and real.' It seemed very funny, the idea of bringing them into an embodied form."

If the Whitney's visitors didn't always know how to react to the bot--some avoided it, others spoke to it as though it were alive--that was the point, Wortzel says.

But beyond the exhibit's artistic value, she is quick to emphasize, were the educational gains made by students and faculty in art and engineering working together on a common project.

Wortzel and Weiman named their course "Design, Illusion and Reality: Equally Avatar: Man, Machines and Virtual Beings." In the class, students ordinarily confined to their respective departments worked together to design the software and audiovisual elements that would later control Kiru during the robot's stint at the Whitney.

The project introduced an element of creativity that is not always present in the lives of engineering students, Wortzel reports, and likewise helped the artists see how science could bring their creative ideas to fruition. Without NSF support and matching funds from Cooper Union, she emphasizes, such an interdisciplinary project would not have been possible.

At first, "the engineering students said, 'tell me what you want to build,' and they would build, and they would think they were done," says Weiman. And "the artists would say, 'This is ugly. It does nothing. It needs a framework, a mission.'"

But by working together, each group gained an appreciation for the possibilities made available by the other. In the end, "we produced projects that went far beyond what either group would have done without the other," Weiman says, adding that "art injected something quite new and valuable into engineering projects, and engineering injected performance into art projects, and…both were on exciting new ground."

It was a fruitful alliance, Wortzel agrees, giving both groups of students an opportunity to pursue creative ideas and gain experience in robotic control and design. The interplay between the practical and the creative, Wortzel says, was by design--much like the Internet itself.

"The students were on completely unknown ground at all times, and had to uncover things through communication and research," Weiman recalls. "And that's what education is all about."

And educational value aside, the project succeeded as art as well. "Data Dynamics" was the first Whitney exhibit to feature the product of an NSF-funded effort.

All of the project's students have now gone on to promising jobs--one of them, for example, now works in the U.S. Navy's premier research and development facility, Wortzel says, and another designs prosthetic limbs at the New York University Medical Center.

As for Kiru, the robot has become part of a permanent laboratory at Cooper Union, called "StudioBlue," where science and art are always welcome to meet.

--Sarah Goforth