Discovery of a new genetic cause of hearing loss illuminates how inner ear works

A gene called GAS2 plays a key role in normal hearing, and its absence causes severe hearing loss, according to a study led by researchers in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

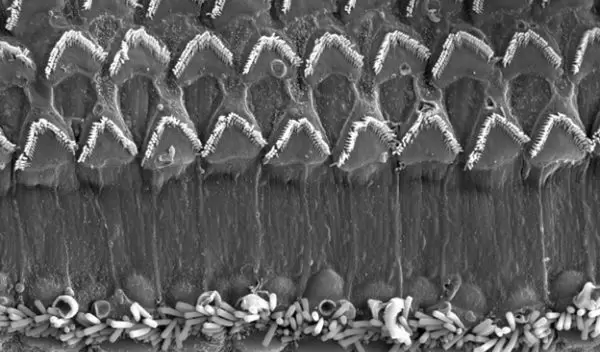

The U.S. National Science Foundation-funded scientists discovered that the protein encoded by GAS2 is crucial for maintaining the structural stiffness of support cells in the inner ear that normally help amplify incoming sound waves. Their findings, published in Developmental Cell, showed that inner ear support cells lacking functional GAS2 lose their amplifier abilities, causing severe hearing impairment in mice. The researchers also identified people who have both GAS2 mutations and severe hearing loss.

"Anatomists 150 years ago took pains to draw these support cells with the details of their unique internal structures, but it's only now, with this discovery about GAS2, that we understand the importance of those structures for normal hearing," said study senior author Douglas Epstein, a geneticist at Penn Medicine.

Two to three of every 1,000 children in the United States are born with hearing loss in one or both ears. About half these cases are genetic. Although hearing aids and cochlear implants often can help, these devices seldom restore hearing to normal.

One of the main focuses of the Epstein laboratory is the study of genes that control the development and function of the inner ear -- genes that are often implicated in congenital hearing loss. The inner ear contains a complex, snail-shaped structure, the cochlea, that amplifies the vibrations from sound waves, transduces them into nerve signals, and sends those signals toward the auditory cortex of the brain.

A few years ago, Epstein's team discovered that Gas2, the mouse version of human GAS2, is switched on in embryos by another gene known to be critical for inner ear development. To determine Gas2's role in that development, the team developed a line of mice in which the gene had been knocked out of the genome.

The prevalence of hearing loss in people due to GAS2 mutations remains to be determined, but Epstein noted that this type of congenital hearing loss is an attractive target for future gene therapy.