Does limited underground water storage make plants less susceptible to drought?

You might expect that plants hoping to thrive in California's boom-or-bust rain cycle would choose to set down roots in a place that can store lots of water underground to last through drought years.

But some of the most successful plant communities in the state -- and probably in Mediterranean climates worldwide, with their wet winters and dry summers -- have taken a different approach. They've learned to thrive in areas with a below-ground water storage capacity barely large enough to hold the water that falls even in lean years.

Surprisingly, these plants do well in both low-water and rainy years precisely because the soil and weathered rock below ground store so little water relative to the rain delivered, NSF-funded scientists at UC Berkeley have found.

As a result, the plants are much more resilient in drought years, as evidenced by California's relatively unscathed North Coast during recent droughts that killed hundreds of millions of trees in the Sierra Nevada.

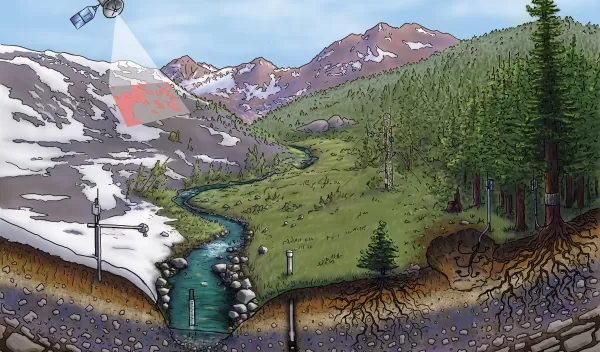

The insights about rock moisture emerged from a long-term project at NSF's Eel River Critical Zone Observatory, where scientists charted the life cycle of water in the environment -- from sky through vegetation, soil and rock into streams, and back up into the atmosphere by evaporation and transpiration.

The researchers describe their findings in a paper recently published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

The research is funded by NSF's Division of Earth Sciences.