Earthquakes in Slow Motion

A new study by researchers at Caltech finds that "slow slip" or "silent" earthquakes -- when faults grind incredibly slowly against each other, as though in slow motion -- behave more like regular earthquakes than previously thought.

A slow-slip event occurring over the course of weeks can release the same amount of energy as a minute-long, magnitude-7.0 earthquake, but because they occur deep in the Earth and release energy so slowly, there is very little deformation at the surface.

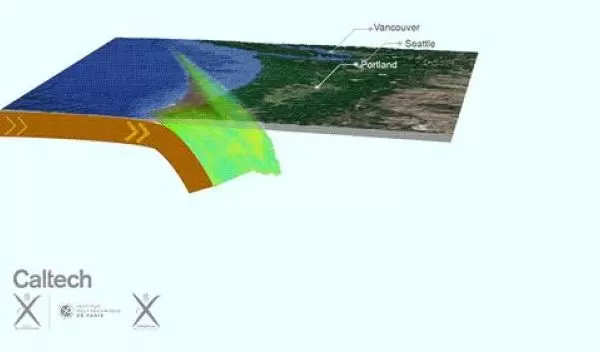

Caltech's Jean-Philippe Avouac and a team of researchers used a network of 352 GPS stations to detect and image slow-slip events along Washington state's Cascadia Subduction Zone, where the North American tectonic plate is sliding southwest over the Pacific Ocean plate. The researchers analyzed data from 2007 to 2018 and built a catalog of more than 40 slow-slip events. Their findings appear in Nature.

The NSF-supported team characterized features of slow-slip events more precisely than previously possible and found that the underlying mechanics of slow-slip earthquakes and regular earthquakes in Cascadia may be the same.

"If we study a fault for a dozen years, we might see 10 of these events," Avouac says. "That lets us test models of the seismic cycle, learning how different segments of a fault interact with one another. It gives us a clearer picture of how energy builds up and is released with time along a major fault." Such information could offer more insight into earthquake mechanics and the physics governing their timing and magnitude, he says.

"This research demonstrates how observations made through NSF's EarthScope Plate Boundary Observatory will continue to have a lasting impact. This project wouldn't be possible without the decade of data provided by the observatory," said Eva Zanzerkia, a program director in NSF's Division of Earth Sciences.