Effect of ‘eddy killing’ in oceans is no longer a matter of guesswork

Ocean currents, propelled by kinetic energy from the wind, are the great moderators of the Earth's climate. By transferring heat from the equator to polar regions, they help make our planet habitable.

And yet, the large-scale models used by scientists to study this complex system fail to accurately account for the impact of wind on the ocean’s most energetic components: swirling, mesoscale eddies. These circular currents of water 50 to 500 kilometers in size are critical to determining the trajectory of larger ocean currents like the Gulf Stream.

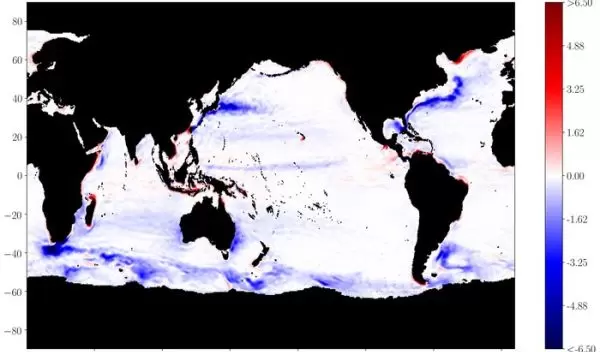

In a U.S. National Science Foundation-funded paper in Science Advances, researchers at the University of Rochester and Los Alamos National Laboratory document for the first time how the wind, which propels larger currents, has the opposite effect on eddies less than 260 kilometers -- resulting in a phenomenon called "eddy killing."

They also provide the first direct measurement of the overall impact of this eddy killing: a continual loss of 50 gigawatts of kinetic energy -- equivalent to the detonation of a Hiroshima nuclear bomb every 20 minutes, year-round.

"For the first time we are able to unravel eddy killing by direct measurements from satellite observations, with minimal assumptions," says corresponding author Hussein Aluie at the University of Rochester.

The team applied a coarse-grained approach to satellite imagery. Doing so allowed the researchers to separate the complex, multiscale structures of ocean currents and eddies embedded in each other.

The method provides a more detailed spatial analysis than is possible with the ones used by most oceanographers, which concentrate on temporal fluctuations, Aluie says. Those methods either fail to account for the impact of eddy killing or provide wildly varying estimates.

Scientists have known about eddy killing since the late 1980s from idealized models, says Aluie.

An eddy is like a circle rotating clockwise or counterclockwise. Any wind flowing over the eddy, however, will be moving in only one direction, "helping" the half of the circle moving at least partly in the same direction, while impeding the other half.

"On the one hand the wind is making the ocean move, and yet it is killing the part of it that is the most energetic. So, it is counterintuitive and something that had not been directly measured before because people were using the wrong tools," Aluie says.

A better tool is important because many questions remain about other factors that may influence eddy killing, and about the importance of eddies in other aspects of the ocean’s currents, heat flow, salt concentrations and upwelling of nutrients and marine organisms, he says. The method demonstrated in this paper will hopefully be adapted by oceanographers to unravel these mysteries, according to Aluie.