Even 'Goldilocks' exoplanets need a well-behaved star

An exoplanet may seem like the perfect spot to set up housekeeping, but before you go there, take a closer look at its star.

Rice University astrophysicists are doing just that, building a computer model to help judge how a star’s own atmosphere impacts its planets, for better or worse.

By narrowing the conditions for habitability, they hope to refine the search for potentially habitable planets. Astronomers now suspect that most of the billions of stars in the sky have at least one planet. To date, Earth-bound observers have spotted nearly 4,000 of them.

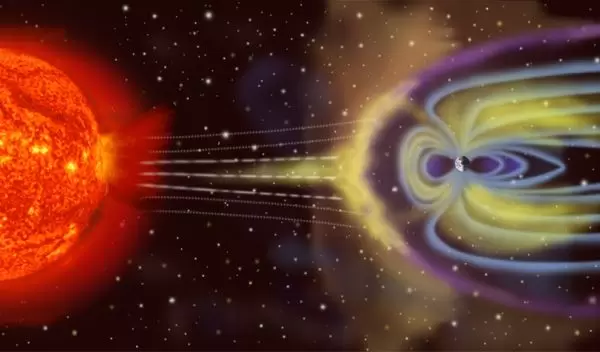

Alison Farrish and David Alexander at Rice led the group’s first study to characterize the "space weather" environment of stars other than our own to see how it would affect the magnetic activity around an exoplanet. It’s the first step in an NSF-funded project to explore the magnetic fields around the planets themselves.

"It’s impossible with current technology to determine whether an exoplanet has a protective magnetic field or not, so this paper focuses on what is known as the asterospheric magnetic field," Farrish said. "This is the interplanetary extension of the stellar magnetic field with which the exoplanet would interact."

In the study, published in The Astrophysical Journal, the researchers expand a magnetic field model that combines what is known about solar magnetic flux transport -- the movement of magnetic fields around, through and emanating from the surface of the sun -- to a wide range of stars with different levels of magnetic activity. The model is then used to create a simulation of the interplanetary magnetic field surrounding these simulated stars.

The research is funded through an NSF award aimed at producing advanced computer models by applying techniques developed by the space physics community to astrophysical research into exoplanets.