Extinct Caribbean bird yields DNA after 2,500 years in watery grave

Scientists have recovered the first genetic data from an extinct bird in the Caribbean, thanks to the remarkably preserved bones of a Creighton's caracara in a flooded sinkhole on Great Abaco Island in the Bahamas.

Studies of ancient DNA from tropical birds have faced two formidable obstacles. Organic material quickly degrades when exposed to heat, light and oxygen. And birds' lightweight, hollow bones break easily, accelerating the decay of the DNA within.

But the dark, oxygen-free depths of a 100-foot blue hole known as Sawmill Sink provided ideal preservation conditions for the bones of Caracara creightoni, a species of large carrion-eating falcon that disappeared soon after humans arrived in the Bahamas about 1,000 years ago.

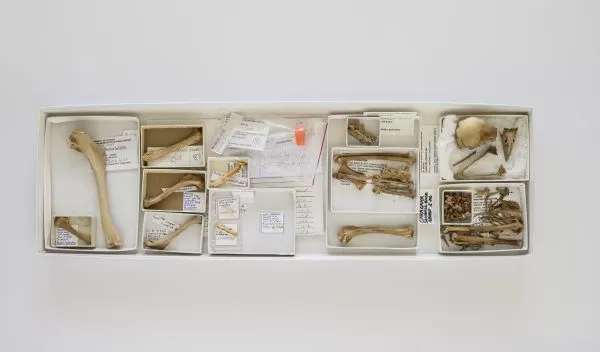

Florida Museum of Natural History researcher Jessica Oswald and her colleagues extracted and sequenced genetic material from the 2,500-year-old C. creightoni femur. Because ancient DNA is often fragmented or missing, the team had modest expectations for what they would find –- maybe one or two genes. But instead, the bone yielded 98.7% of the bird's mitochondrial genome, the DNA most living things inherit from their mothers.

The mitochondrial genome showed that C. creightoni is closely related to the two remaining caracara species alive today: the crested caracara and the southern caracara. The three species last shared a common ancestor between 1.2 and 0.4 million years ago.

The researchers published their findings in the journal Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution.

"This project enhanced our understanding of the ecological and evolutionary implications of extinction, forged strong international partnerships, and trained the next generation of researchers," says Jessica Robin, a program director in NSF's Office of International Science and Engineering, which funded the study.