Fake Drugs Exposed by Rapid Chemical Assay

Researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology developed a rapid chemical assay based on mass spectrometry to screen the quality of artesunate-based antimalarial drugs in Southeast Asia and several African countries. They used the assay to test the quality of hundreds of tablets in a short period of time. Their work allowed an international team to make evidence-based suggestions as to where some of the fake artesunate was manufactured. Armed with this information, authorities in China and the International Criminal Police Organization, or INTERPOL, acted quickly to stop counterfeit production and dissemination.

Malaria remains one of the world's largest public health problems, causing about 500 million cases of illness and at least one million deaths per year. Drug therapies with the active ingredient artesunate have become vital to treating malaria as the parasite that causes the disease is now resistant to many older drugs. Unfortunately, drug counterfeiters in Southeast Asia produce and sell drugs containing fake artesunate, which has led to avoidable deaths and reduced confidence on the part of patients, health care workers and others in this effective drug treatment. It also has resulted in large economic losses for legitimate manufacturers.

"Drug counterfeiting is a multi-billion-dollar business," said Facundo M. Fernandez, professor of chemistry at the Georgia Institute of Technology. "Because penalties for drug counterfeiting are typically more lenient than penalties for illegal drug trafficking, counterfeiting is becoming a popular way of life for criminals and terrorists looking to make a fast profit with minimum risk."

Fernandez and his team at Georgia Tech, with support from the National Science Foundation, joined an international collaboration of scientists, police and health care workers led by Paul Newton, a scientist with the Oxford Tropical Medicine Southeast Asia Research Collaboration, to conduct forensic analyses of samples of genuine and counterfeit artesunate. Their analysis uncovered 16 different counterfeit versions with little or no artesunate. The team also discovered the presence of illegal or improper active pharmaceutical ingredients in the counterfeit drugs; for example, metamizole, a powerful painkiller and fever reducer that is now banned.

"This illustrates how fundamental research supported by the NSF can have broad, practical implications affecting many people," said NSF Program Officer Kelsey Cook. "Sometimes the path from fundamental work to important impacts is slow and almost imperceptible. In this case, it has happened relatively quickly. The importance of supporting high-quality fundamental research is that it is rarely possible to know which advances in basic understanding will have such impact, let alone how quickly."

Working under the auspices of INTERPOL, and the Western Pacific World Health Organization Regional Office, the researchers developed a rapid chemical assay that is similar to assays used by the FBI to analyze samples collected at crime scenes.

"We are now working on improving their sensitivity by better understanding the phenomena that affect ion transport at the interface of the ion source and the mass spectrometer," Fernandez said. "We've recently expanded our assays to a new test to verify the authenticity of Tamiflu, a medicine to treat influenza which has been in very high demand in the last few years due to fears of a pandemic."

Their assay included a variety of chemical techniques, including two different direct ionization mass spectrometry methods known as Direct Analysis in Real Time and Desorption Electrospray Ionization. They complemented these with analyses performed by Michael Green at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography and rapid colorimetric testing to confirm that all specimens thought to be counterfeit on the basis of packaging contained little or no quantities of artesunate. A biological analysis of pollen grains inside the packages indicated the counterfeit samples originated in Southeast Asia along the Chinese border.

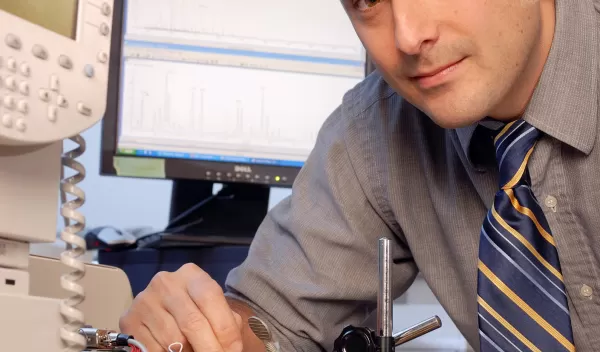

"We operate by giving INTERPOL officers forensic results as fast as we can respond," Fernandez said. "This is on-going work that involves graduate and undergraduate students, who analyze these samples as side projects. I think there is tremendous educational value in these activities because students not only do their normal research toward a degree, but they are also exposed to real world applications, which is crucial for their development as professionals."

Inside the United States, the Food and Drug Administration has forensic laboratories to analyze samples, but they are mainly concerned with potentially fake or low-quality medicines that are found in the U.S.

"What is unique about the international collaboration and our work at Georgia Tech, is that we have applied cutting-edge research in new analytical separation and detection methods to a problem that affects a large number of people in developing countries," Fernandez said. "This type of problem tends to fall through the cracks as developing countries don't have the necessary resources to combat organized drug counterfeiters."