Fantastic Fungus: Plant Biologist Discovers Natural Antimicrobial in Honduran Jungle

The gold rush era may be over, but in Montana another type of globetrotting prospector is making news. Montana State University biologist Gary Strobel has spent much of the past two decades rummaging in the planet's remaining rain forests for treasures in twigs and stems. And he's sharing his spoils with the world.

It isn't the plants themselves that most interest Strobel. Back at his laboratory, he inspects the cuttings he has collected for the precious bounty they carry: the bacteria and fungi that live inside, known to biologists as endophytes. Strobel screens the organisms--and the gases and other waste products they give off--looking for potential drugs, pesticides or other useful compounds.

Sometimes what he finds is very useful--and surprising. In 1999, Strobel opened a plastic tray in his Montana State University laboratory and thought for a minute that his recent expedition to the Honduran rain forest had been a bust. Of the dozen or so species of fungi he had collected there, all had survived the trip. But after Strobel placed them in a shared container to prevent infestation from mites in the laboratory, all but one died after a few days.

At first, Strobel was perplexed. But then came a Eureka moment.

He recalls: "You ask yourself, 'Why did all of them die?' But it was all but one. It must have killed everything else. Fumes." On closer inspection, Strobel found that a fungus collected from a cinnamon tree had effectively conducted gas warfare on the other specimens.

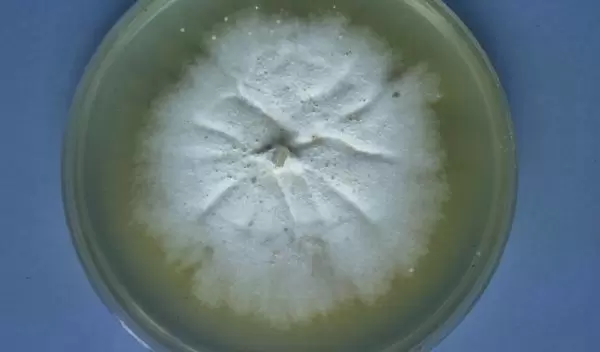

Strobel named the killer fungus Muscodor albus, Latin for "stinky white fungus." He and his colleagues found more than 30 ingredients in the fumes released by M. albus, none of which are toxic to mammals or plants on their own. But combined, the volatile chemicals proved to be a deadly recipe.

"This little thing is a chemical factory," says Strobel. "When we put all the chemicals together in the same ratio, we can reproduce its effect against other microbes. You can grow it on one half of a plate and put almost any microbe on the other side and [the microbe] will grow for an hour and die."

With support from the National Science Foundation's Division of Chemistry, Strobel's group recreated M. albus' signature fumes with chemicals purchased from a supply company. When tested as a fumigant, the gas prevented the growth of several common agricultural pests, like the smut fungus Ustilago hordei, water mold and root rot. Within a year, Strobel and Montana State University received a patent on the chemical recipe.

Despite the quick success Strobel has found with this fungus, it takes patience to develop new products by his approach. There are 300,000 plant species on Earth, and even more species of endophytes. Of the few endophytes that have been studied, only a fraction have proved useful to researchers. After the specimens are collected, the real work begins in the laboratory. Potential compounds are identified, and later tested for usefulness, safety and ease of production. The total cost for the development of a new product can be upward of $300 million, Strobel says.

But occasionally, the rewards are great. The cancer-fighting compound taxol was first isolated from the Pacific yew tree. But for years after the drug's discovery, production was difficult because the tree is rare and produces taxol in only small amounts. Synthesizing taxol in the lab is costly. In 1993, Strobel and his colleagues made a surprising discovery: a fungal endophyte living in the yew tree's needles produces taxol as well. Since then, researchers have cultured the fungus in the laboratory to produce the drug in large quantities without harvesting the trees.

After that experience, Strobel thought about the thousands of undiscovered endophytes living among the rich flora of the remaining rain forests. "Who knows what could be out there," he recalls thinking. Now he circles the globe--going from China to Brazil to the islands off the African shore--to find out.

"There are about 2 to 3 million people every year who die of malaria. There are about 3 million who die of tuberculosis. There are 7 to 8 million people who die of AIDS," Strobel points out. "And in our present society there are untold numbers of people dying of drug-resistant bacteria. We thought we had them under control until they mutated. So we need new drugs."

But endophytes' potential usefulness goes beyond pharmaceuticals. Phillips Environmental Products, a company in Belgrade, Montana, has licensed Strobel's stinky white fungus for the company's commercial line of portable toilets. The toilets--used by the American military and also in national parks and a variety of emergency situations--are now equipped with waste collection bags containing deactivated fungus. When moisture enters the bag, the fungus will produce its natural fumes, neutralizing odor and killing a host of dangerous bacteria, including E. coli. The company is currently seeking Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) approval for the product.

Strobel believes the technology also holds tremendous promise for the developing world, where intestinal diseases resulting from poor sanitary conditions are among the major causes of death.

Another company interested in M. albus is California-based AgraQuest. The conglomerate recently received EPA approval to develop the fungus for a number of agricultural applications, most notably to kill microbes that would otherwise cause the decay of fruits and vegetables during shipment and storage.

"The idea is to put the fungus in a little wet packet, place it in a box of produce, and it will take care of the pathogens. It's simple and natural," explains Strobel.

If the AgraQuest product is successful in the market, it could be a safe and natural alternative to the caustic chemical methyl bromide, which depletes ozone, contaminates soil and can be harmful to human health. Since January 2005 the EPA has been phasing out use of methyl bromide except for certain purposes, mainly agricultural, where there is no technical or economically feasible alternative.

M. albus won't be the first endophytic species to make a name for itself in industry, not by a longshot. A range of existing products have endophyte origins, including antibiotics, antiviral compounds, anticancer agents, antioxidants, insecticides, antidiabetic agents and immunosuppressive drugs used to prevent organ rejection in transplant patients.

For years, Strobel served as Montana's state project director of the Experimental Program to Stimulate Competitive Research (EPSCoR), a partnership between NSF and 24 states and 2 territories that promotes the development of science, engineering, technology and related human resources in those regions.

The Montana researcher--now 67--doesn't plan to move to the sidelines anytime soon. Strobel is planning an excursion to Peru's upper Amazon in 2006. "We still need new drugs," especially those for treating the infectious diseases that plague the developing world, he says. "What better place to find them?"

-- Sarah Goforth