'Far out' blazar discovery suggests early universe had more supermassive black holes than previously thought

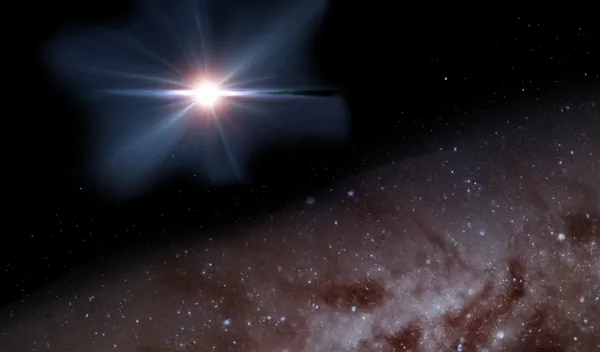

Scientists have discovered the most distant and therefore oldest blazar ever seen. Labeled J0410–0139, the blazar is at the center of a galaxy 12.9 billion light years away and provides a rare glimpse into what the universe was like when it was less than 800 million years old.

The discovery challenges scientists' current notions about the early universe, especially black holes. Namely: how big they could get, how fast they could grow, and how many could have existed. The findings are published in Nature Astronomy and The Astrophysical Journal Letters and made possible by multiple facilities, including the U.S. National Science Foundation Very Large Array, the NSF Very Long Baseline Array, the Chandra X-ray Observatory and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA).

Detecting a blazar is rare to begin with. A blazar is a type of active galactic nucleus, or "AGN" for short. Supermassive black holes, sometimes millions to billions of times larger than the sun, are found within these nuclei. When feeding on matter, these black holes may project jets of charged particles shooting out in two directions and at almost the speed of light. If it is apparent that a jet is pointed almost directly at the viewer, the object is classified as a blazar.

With the jet of the blazar pointed right at Earth, one can see deep inside the galaxy to very near the supermassive black hole and hence learn more about the jet itself and, ultimately, the black hole. Says Joe Pesce, NSF program director for the NSF National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NSF NRAO), "This observation adds to a body of findings indicating that supermassive black holes in the early universe aren't acting like we thought they should."

"These observations are surprising because we don't seem to understand supermassive black hole formation as well as we thought," adds Pesce. "But they are also exciting because it's a new mystery that we have to solve, and in doing so, we will learn more about the universe and how it works."

"This blazar offers a unique laboratory to study the interplay between jets, black holes, and their environments during one of the universe's most transformative epochs," says Emmanuel Momjian of NSF NRAO and co-lead of the study, "The alignment of J0410−0139's jet with our line of sight allows astronomers to peer directly into the heart of this cosmic powerhouse."

J0410–0139 is the farthest cosmic object of its kind ever seen — meaning it is earlier and "older" than any similar AGN ever detected. A distant blazar sighting like this indicates that supermassive black holes from this epoch may grow even faster than previously thought or that they are "born" even larger in size during this period than earlier theorized, suggests the research.

Plus, says Silvia Belladitta, a postdoc author of the study: "Where there is one, there's one hundred more." Eduardo Bañados, first author of the paper, adds, "Finding one AGN with a jet pointing directly towards us implies that at that time, there must have been many AGN in that period of cosmic history."

Like seeing a cockroach in your home, one blazar sighting could mean there are hundreds — maybe even thousands — of other AGNs from the same period that aren't visible or just not observed yet. The finding thus suggests that supermassive black holes, like those found within this most distant blazar, might be more commonplace during the ancient beginnings of the universe than thought.