Fossil evidence of 'hibernation-like' state in 250-million-year-old Antarctic animal

Hibernation is a familiar feature on Earth today. Many animals -- especially those that live close to or in polar regions -- hibernate to get through tough winter months when food is scarce, temperatures drop and days are dark.

According to new U.S. National Science Foundation-funded research, this type of adaptation has a long history. In a paper in the journal Communications Biology, scientists at the University of Washington report evidence of a hibernation-like state in an animal that lived in Antarctica during the Early Triassic, some 250 million years ago.

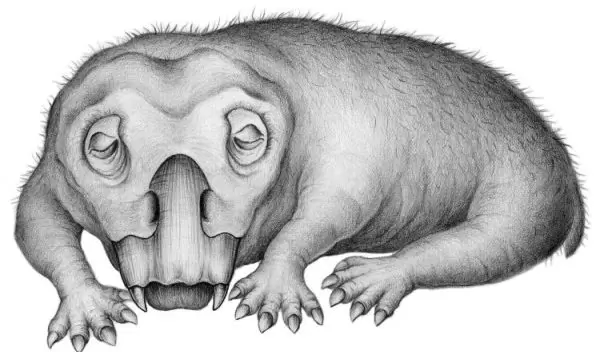

The creature, a member of the genus Lystrosaurus, was a distant relative of mammals. Antarctica during Lystrosaurus' time was largely within the Antarctic Circle, like today, and experienced extended periods without sunlight each winter.

The fossils are the oldest evidence of a hibernation-like state in a vertebrate animal, and indicate that torpor -- a general term for hibernation and similar states in which animals temporarily lower their metabolic rates to get through a tough season -- arose in vertebrates before mammals and dinosaurs evolved.

Lystrosaurus lived during a dynamic period of our planet's history, arising just before Earth's largest mass extinction at the end of the Permian Period -- which wiped out about 70% of vertebrate species on land -- and somehow survived it. The stout, four-legged foragers lived another 5 million years into the subsequent Triassic Period and spread across Earth's then-single continent, Pangea, which included what is now Antarctica.

"The fact that Lystrosaurus survived the end-Permian mass extinction and had such a wide range in the early Triassic has made them a very well-studied group of animals for understanding survival and adaptation," said co-author Christian Sidor, a University of Washington vertebrate paleontologist.

Added Michael Jackson, a program director in NSF's Office of Polar Programs, "The abundance of correct age rocks and relevant fossils found in the Shackleton Range of Antarctica allows scientists to understand how past life evolved at high latitudes, and to study the unexpected physiological flexibility in Lystrosaurus."