Fossil pollen samples suggest vulnerability to extinctions ahead

Reduced resilience of plant biomes in North America could be setting the stage for the kind of mass extinctions not seen since the retreat of glaciers and arrival of humans about 13,000 years ago, cautions new research published in the journal Global Change Biology.

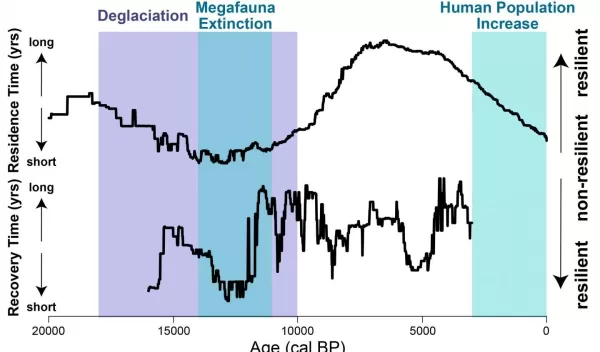

The warning comes from a study of 14,189 fossil pollen samples taken from 358 locations across the continent. Scientists at Georgia Tech used data from the samples to determine landscape resilience, including how long specific landscapes such as forests and grasslands existed, a factor known as residence time, and how well they rebounded following perturbations such as forest fires, a factor termed recovery.

"Our work indicates that landscapes today are exhibiting low resilience, foreboding potential extinctions to come," wrote co-authors Yue Wang, Benjamin Shipley, Daniel Lauer, Roseann Pineau and Jenny McGuire. "Conservation strategies focused on improving both landscape and ecosystem resilience by increasing local connectivity and targeting regions with high richness and diverse landforms can mitigate these extinction risks."

The study, supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation, is believed to be the first to quantify biome residence and recovery time over an extended period. The researchers studied 12 major plant biomes in North America over the past 20,000 years using pollen data from the Neotoma Paleoecology Database.

The scientists discovered that landscapes today are experiencing resilience lower than any seen since the end of the Pleistocene megafauna extinctions, animal extinctions that occurred about 12,700 years ago.

By studying the mix of plants represented by pollen samples, the researchers found that over the past 20,000 years, forests persisted longer than grasslands -- averaging 700 years versus about 360 years -- though they also took much longer to reestablish after being perturbed, 360 years versus 260 years.

The effects of climate change and human environmental impacts don't bode well for the future of North American plant biomes, but there are ways to address that, Wang said. "We know that strategies exist to mitigate some of these effects, such as prioritizing biodiverse regions that can rebound quickly, and increasing the connectivity between natural habitats so species can move in response to warming."

Added Diana Pilson, a program director in NSF's Division of Environmental Biology, "This 20,000-year pollen record shows a reduction in landscape resilience with more rapid changes in temperature. It provides a sobering warning about the potential for mass extinctions in the near future."