'Gone Bats' Over Aeroecology

By the dark of the Halloween new moon, scientists are looking at what's hovering just above the ground.

Far from ghost-busting, however, the researchers are using sophisticated technology like Doppler weather radar to study the aerosphere--the air and the organisms that migrate and feed within it.

Biologists and atmospheric scientists are engaged in the study of aeroecology: how and why airborne organisms--bats, birds, arthropods and microbes--depend on the support of the atmosphere closest to Earth's surface.

In contrast to animals with a strictly terrestrial or aquatic existence, said aeroecologist Thomas Kunz of Boston University, those that routinely use the aerosphere are immediately influenced by changing atmospheric conditions like winds, precipitation, air temperature, sunlight--and moonlight.

Kunz and others published results of their research on aeroecology in a special issue of the journal Integrative & Comparative Biology (July 2008): "Aeroecology: Probing and Modeling the Aerosphere--The Next Frontier."

"The air is full of life, often unnoticed," said Elizabeth Blood, program director in NSF's Division of Biological Infrastructure, which funds Kunz's research. "The skies hold secrets about animals that live at least part of their lives there. Research in aeroecology is opening a window into this unseen world."

Information in the aerosphere, scientists are finding, can help us understand how animals respond to altered landscapes and atmospheric conditions.

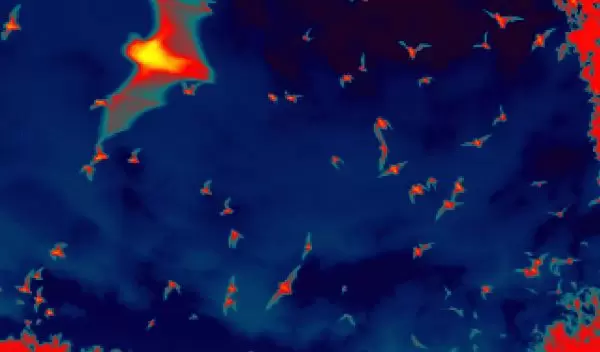

Thermal imaging cameras, which record temperature profiles of animals usually invisible at night, allow biologists to count numbers of animals like Brazilian free-tailed bats.

"Using NEXRAD Doppler weather radar, we can distinguish the movements of birds vs. bats, based on their patterns of daily and nightly dispersal," said Kunz. "With NEXRAD radar, we can also identify and document the movements of animals during migration."

Organisms that use the aerosphere, like birds and bats, are influenced by an increasing number of man-made conditions and structures: lighted towns and cities, air pollution, skyscrapers, aircraft, radio and television towers, and communication towers and wind turbines.

"In addition, human-altered landscapes are affected by deforestation, intensive agriculture, urbanization and industrial activities," said Kunz. "These factors are rapidly and irreversibly transforming the habitats upon which airborne organisms rely."

Conditions in the aerosphere affect navigational cues, sources of food and water, and nesting and roosting habitats.

"Climate change, with its expected increase in global temperatures, altered circulation of air masses and effects on local and regional weather patterns, will have profound impacts on the foraging and migratory behavior of bats, birds and insects," said Kunz.

Aeroecology integrates atmospheric science, earth science, geography, ecology, computer science, computational biology and engineering.

"In the history of science and technology, every so often discoveries, theories and technological developments converge," said Kunz, from which bubbles up a new field.

He cites past examples: marine biology, biomechanics and astrobiology. And more recently, nanotechnology and bioinformatics. "All are disciplines now well established in the lexicon of modern science and technology," he said.

According to Kunz, scientists who study the aerosphere face three important challenges:

- Discovering the best methods for detecting the presence, identity, diversity and activity of organisms that use this aerial environment;

- Identifying important environmental variables at different time and space scales;

- Determining how best to understand and interpret behavioral, ecological and evolutionary responses of organisms within the context of complex meteorological patterns, and linking that information with both natural and human-altered environments.

"Understanding the lives of organisms aloft can help us with important ecological and evolutionary concepts," said Kunz.

Aeroecology also will provide answers to questions, he said, about the spread of invasive species, emergence of infectious diseases, declining biodiversity and sustainability of terrestrial, aquatic and aerospheric environments--whether by darkest night or brightest day, by new moon or full.