Healthy sleep may rely on long-overlooked brain cells

For something we spend one-third of our lives doing, we still understand remarkably little about how sleep works -- for example, why can some people sleep deeply through any disturbance, while others regularly toss and turn for hours each night? And why do we all seem to need a different amount of sleep to feel rested?

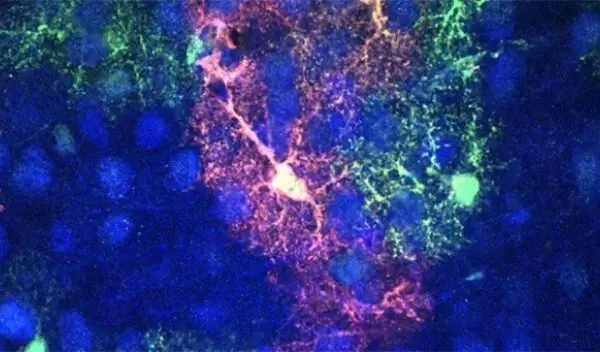

For decades, scientists have looked to the behavior of the brain's neurons to understand the nature of slumber. Now, though, researchers at the University of California, San Francisco have confirmed that a different type of brain cell that has received far less study -- astrocytes, named for their star-like shape -- can influence how long and how deeply animals sleep. The findings of the U.S. National Science Foundation-funded research could open new avenues for exploring sleep disorder therapies and help scientists better understand brain diseases linked to sleep disturbances, such as Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, the authors say.

"This is the first example where someone did an acute and fast manipulation of astrocytes and showed that it was able to affect sleep," said Trisha Vaidyanathan, the study's first author. "That positions astrocytes as an active player in sleep."

When we're awake, our brains are a complex chorus of neuronal voices chattering among themselves to allow us to work through life's daily tasks. But when we sleep, the voices of signaling neurons meld into a unified chorus of bursts, which neuroscientists call slow-wave activity. Recent research had suggested that astrocytes, not just neurons, may help trigger this switch.

Astrocytes make up an estimated 25% to 30% of brain cells. They are a type of so-called glial cell that blankets the brain with countless bushy tendrils. This coverage allows each individual astrocyte to listen in on tens of thousands of synapses, the sites of communication between neurons. The plentiful cells connect to each other through specialized channels, which researchers think may allow astrocytes located across the brain to function as one unified network. The hyperconnected and ubiquitous astrocytes might be able to drive synchronized signaling in neurons, as suggested by the new study, published in eLife.

"This study indicates an unexpected role in controlling sleep for these star-shaped cells that are not neurons, but are very abundant and important in the brain," said John Godwin, a program director in NSF's Division of Integrative Organismal Systems.