Hidden in African diamonds, a billion-plus years of deep-Earth history

Diamonds are sometimes described as messengers from the deep Earth; scientists study them closely for insights into the otherwise inaccessible depths from which they come. But the messages are often hard to read.

Now, a U.S. National Science Foundation-funded study published in Nature Communications solves two long-standing puzzles: the ages of individual fluid-bearing diamonds, and the chemistry of their parent material. The results have allowed scientists to sketch out geologic events going back more than a billion years -- a potential breakthrough not only in the study of diamonds, but of planetary evolution.

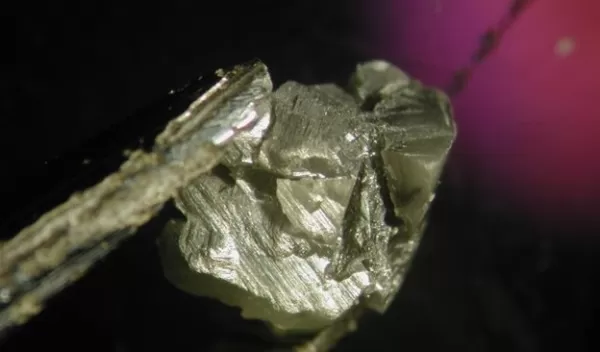

Gem-quality diamonds are nearly pure lattices of carbon. This elemental purity gives them their luster, but it also means they carry very little information about age and origin. However, some lower-grade specimens harbor imperfections in the form of tiny pockets of liquid -- remnants of the more complex fluids from which the crystals evolved.

By analyzing these fluids, the scientists determined when the diamonds formed, and the shifting chemical conditions around them.

"It opens a window -- even a door -- to some of the really big questions about the evolution of the deep Earth and the continents," said lead author Yaakov Weiss, a geochemist at Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. "This is the first time we can get reliable ages for these fluids."

New layers can be added to old crystals, the team found, allowing individual diamonds to evolve over vast periods of time.

It was at the end of the most recent time period, when Africa had formed its current shape, when volcanic eruptions carried the diamonds to the surface. The solidified remains of these eruptions were discovered in the 1870s and became part of the famous De Beers mines. Exactly what caused the eruptions is still part of the puzzle.