Invasive Neighbors Disturb Taiwan's Coasts

When I was offered a chance to study in Taiwan, I was very excited for the opportunity to do environmental research in a different part of the world. But, I was also nervous about living in Asia. My only experiences with Asian culture before visiting Taiwan came from eating Chinese food and watching people eat starfish on "The Amazing Race."

Would studying in a different environment be worth braving the unknown?

The answer, of course, is a solid yes. I received an East Asia and Pacific Summer Institutes (EAPSI) fellowship from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to study in Taiwan in the summer of 2010. EAPSI partnered with Taiwan's National Science Council to send 25 graduate students from the United States to Taiwan last year to foster international collaborations between the two countries.

My host was Hwey-Lian Hsieh of Academia Sinica in Taipei, Taiwan, who researches food webs--the energy and nutrient linkages between all the organisms in an ecosystem.

My own doctoral work focuses on forests of mangrove trees that live right on the edge of the ocean. For the EAPSI fellowship, my research linked our interests through a study of Taiwanese mangrove food webs that are being disrupted by an invasive species.

Invasive studies

Invasive species are important to study because they can alter the way that ecosystems work. The invaders disturb predator-prey dynamics, make native species less abundant and reduce native species biodiversity--changes that cause economic and environmental damage at sites worldwide.

In Taiwan, mangroves colonize coastal mudflats. Cordgrass grows in mudflats on the eastern coast of the United States, and decades ago, it was imported to China for aquacultural purposes. Cordgrass has since spread to Taiwan, where it is thriving despite eradication efforts.

The invasive species that scientists usually study compete directly with a similar native species, often causing the native species to die back. Unlike other invasive species, cordgrass does not replace or directly compete with native species in Taiwan--instead it occupies vacant mudflat space next to mangrove forests.

So I wanted to know: how does an invasive species affect neighboring native ecosystems?

Studying marshes

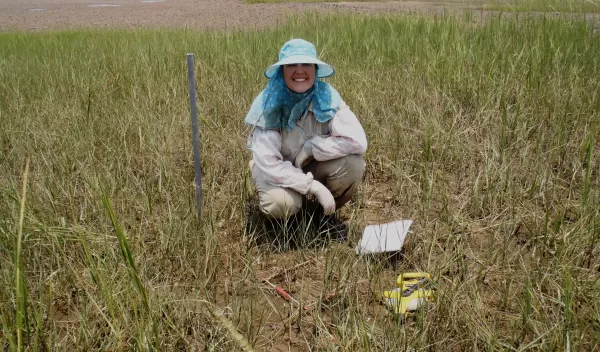

To answer this question, I focused on mudflat food webs. I put crabs and snails that normally eat mangrove materials into cages at the edge of the mangrove forest and provided them with food made from mangrove trees, cordgrass or both types of plants. The results will tell me whether those marsh animals prefer to eat food from mangroves or cordgrass, and how their diet in an invaded marsh will affect their growth and survival.

I also surveyed marshes around Taiwan to determine whether the animals' food preferences affect their foraging strategies. For example, if you're a crab living in the mangrove trees but you would rather eat cordgrass, will you change where and how you eat so you can get your favorite food?

I have many samples left to analyze, but I expect my results to show that the effects of an invader can reach beyond the borders of the invaded area to affect organisms next door.

The creatures that eat mangrove materials play an important role in mangrove ecosystems. They link plant materials and predators in coastal food webs, and their eating habits can influence the type and location of mangroves on mudflats. If marsh animals change the way they eat because of the cordgrass invasion, this could trigger changes in mangrove forests. The forests, when healthy, are a valuable source of food and provide humans with protection from storms on tropical coastlines.

Time in Taiwan

Studying in Taiwan not only advanced my scientific career, it also broadened my view of Asia. The best part of my EAPSI experience was that I didn't just sample some interesting food and landmarks the way a tourist would. I was introduced to the country as an insider because of the connections I had with my Taiwanese lab mates.

I went to a wedding, learned not to question the wisdom of ancient Chinese medicine, got to see parts of Taiwan that are not on tourist maps and discovered what it was like to be a typical Taiwanese student. Because of my host advisor and lab mates, Taiwan will forever be a special place for me.

I am a field ecologist and because I work outside, I can't create the environment I want to study. I have to study the environment that is already there. The EAPSI program gave me the opportunity to research a globally significant issue in a unique scientific setting. There are only a few places in the world where an invasive species has moved in as a neighbor to a native species without replacing it, and Taiwan was an ideal setting for a well-organized scientific study. Understanding how invaders can affect nearby ecosystems is an important step forward in preserving native communities and mitigating the effects of invaders all over the globe.

EAPSI let me connect with scientists abroad in a two-way exchange of scientific and cultural practices. Although I didn't try any starfish, I grew immensely, both professionally and personally, because of my experience.

--Virginia G. W. Schutte, Odum School of Ecology, University of Georgia, vschutte@uga.edu

This Behind the Scenes article was provided to LiveScience in partnership with the National Science Foundation.