Learning to Pivot in the Commercial World

The National Science Foundation's Innovation Corps (I-Corps) program helps scientists assess how and whether they can translate their promising discoveries into viable commercial products. But sometimes the path to the marketplace doesn't always go in a straight line.

Satish Kandlikar, for example, a professor of mechanical engineering at the Rochester Institute of Technology, developed a better way to cool L.E.D. fixtures, which are used in a wide range of lighting applications. But his invention, which he says cooled L.E.D.s more effectively than existing technology, thus helping them last longer, proved too expensive for the market to bear.

"Normal L.E.D.s have a heat dissipation problem," says Kandlikar, an expert in fuel cells, flow boiling. critical heat flux, contact line heat transfer and advanced cooling techniques. "When they heat up, they lose their efficiency and don't last long."

So he and his students created a new device to replace the "heat sinks," or aluminum fins that are standard on L.E.D.s, but not very effective, according to Ankit Kalani, a doctoral student working with Kandlikar.

"The L.E.D. gives out heat, and the aluminum fin around it is supposed to dissipate that heat, but it doesn't work all that well," he says. "The L.E.D.s are supposed to last five to ten years, but they don't last half that long because they aren't getting cooled."

The scientists fashioned a new type of heat pipe that uses liquid for cooling, either water or ethanol. The pipe is made of copper with a novel dimpled internal surface that enhances heat transfer. The researchers say it works vastly better than the aluminum fins at cooling things down. "You need a surface that will boil the water more efficiently," Kandlikar says. "The fluid takes the heat away. The fluid has better thermal properties, so it will always work better than a solid."

The problem, however, was that the technology would have raised the price of a standard L.E.D. fixture by as much as $15, a hefty increase about three times the cost of the L.E.D. without it, a hike that almost certainly would have made the products unaffordable.

"Our idea was too expensive for the product," Kandlikar says. "No one would buy an L.E.D. that was even 50 cents higher than the competition, and ours would've been at least $10 more expensive. So we aren't going forward with the idea as originally conceived."

In the fall of 2011, Kandlikar was among the first group of scientists to receive a $50,000 I-Corps award, which supports a set of activities and programs that prepare scientists and engineers to extend their focus beyond the laboratory into the commercial world, with the idea of providing near-term benefits for the economy and society.

It is a public-private partnership program that teaches grantees to identify valuable product opportunities that can emerge from academic research, and offers entrepreneurship training to student participants.

Occasionally, however, things don't turn out as originally planned, as was the case with Kandlikar's concept. Nevertheless, this outcome embodies the I-Corps philosophy, since one of its major goals is to mentor scientists in ways that allow them to evaluate the commercial potential of their discoveries, and send them in different directions if necessary to ensure their research ends up in the best possible place to do the most good at an affordable price.

"It is not uncommon for teams to alter, sometimes drastically, their projects in response to their finding in the I-Corps curriculum," says Errol Arkilic, an I-Corps program director. "The customer development process used in I-Corps embraces these changes; they are known as pivots, and are a hallmark of the program."

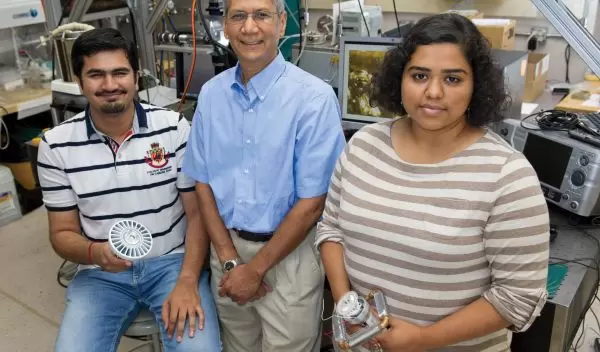

After concluding that the L.E.D. market was not the right one, Kandlikar and his group of students, including Kalani and Kirthana Kripash, turned toward identifying other goods that could benefit from their technology--without resulting in prohibitively expensive pricing--and now are exploring higher end products with the cooling needs, such as computer chips and laser diodes, as well as processes involved in the production of petrochemicals, in air liquefaction and even nuclear reactor cooling.

To that end, Kandlikar has formed a company, Arka Solutions ("Arka" means "sun" in Sanskrit) to further develop his product, and identify the best product "where we can apply this technology," he says.

"For some of these industries, to invest some money in using this technology would provide a huge payback," he adds. "An L.E.D. is only about $5, so to jack it up to $20 would have a huge impact. But in these industries, which involve bigger expenditures, the reward of investing in this technology would be much higher."