LIGO-Virgo finds mystery object in gap between neutron stars and black holes

When the most massive stars die, they collapse under their own gravity and leave behind black holes. When stars that are a bit less massive die, they explode in supernovas and leave behind dense, dead remnants called neutron stars.

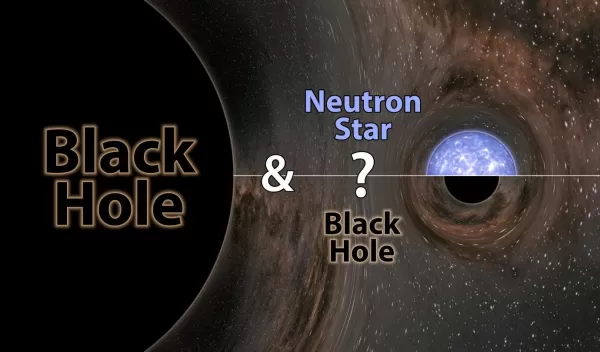

For decades, astronomers have been puzzled by a gap that lies between neutron stars and black holes. The heaviest known neutron star is no more than 2.5 times the mass of our sun, or 2.5 solar masses, and the lightest known black hole is about five solar masses. The question remained: Does anything lie in this so-called mass gap?

In a study by scientists affiliated with the National Science Foundation's Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory and the Virgo detector in Europe, scientists have announced the discovery of an object of 2.6 solar masses, placing it firmly in the mass gap.

"The mass gap has been an interesting puzzle for decades, and now we've detected an object that fits just inside it," said Pedro Marronetti, a program director in NSF’s Division of Physics. "This observation is another example of the transformative potential of the field of gravitational-wave astronomy, which brings novel insights to light with every new detection."

The object was found on August 14, 2019, as it merged with a black hole, generating a splash of gravitational waves detected on Earth by LIGO and Virgo. The findings are published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

"We've been waiting decades to solve this mystery," says co-author Vicky Kalogera of Northwestern University. "We don't know if this object is the heaviest known neutron star or the lightest known black hole, but either way it breaks a record."

The cosmic merger described in the study, an event dubbed GW190814, resulted in a final black hole about 25 times the mass of the sun (some of the merged mass was converted to a blast of energy in the form of gravitational waves). The newly formed black hole lies about 800 million light-years away from Earth.

"This discovery will change how scientists talk about neutron stars and black holes," says co-author Patrick Brady of the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.