Long ago, but not so different

In a new study, a team of U.S. National Science Foundation-supported researchers suggests that 4 billion years ago, plate tectonics likely looked closer to what we experience today than previously thought. The team published its findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science.

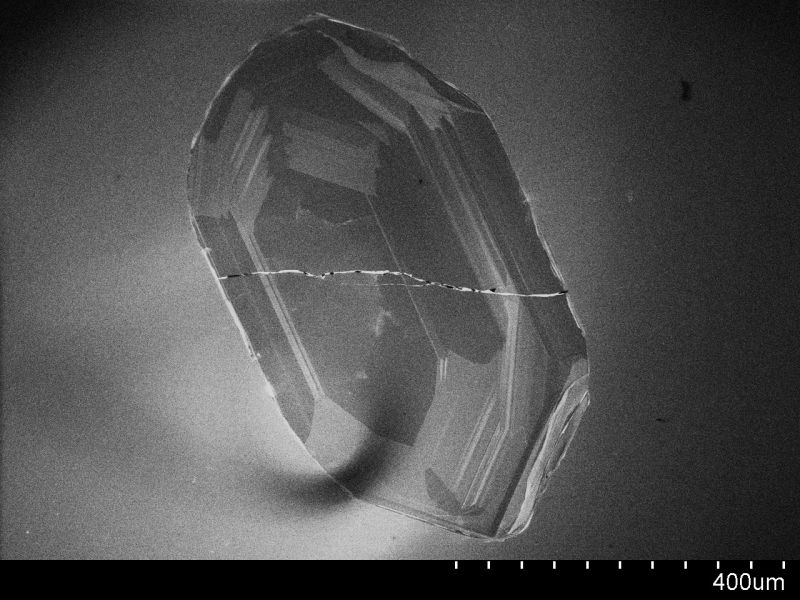

The team studied the mineral zircon from two of the oldest pieces of intact crust — dating 4.0 to 2.7 billion years old — and discovered that ancient plate tectonics, or how the continents move around and interact with each other, was likely just as diverse as it is today.

"Plate tectonics makes our planet uniquely dynamic on a solar system scale," said Emily Mixon, the study’s lead author and a researcher at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. "It has been hypothesized that because plate tectonics is important for moving carbon and water around on long time scales, it might be important for how life evolved on Earth."

Moving continents are destructive — crustal rocks are destroyed and recycled. To reveal the ancient processes behind tectonics, the researchers studied zircons, which are physically durable and resistant to chemical alterations.

More specifically, they studied zircons in the 3.9 – 2.7-billion-year-old Saglek-Hebron Complex and 4.0 – 3.4-billion-year-old Acasta Gneiss Complex and found that instead of a linear progression of tectonic styles, from volcanic lavas and magmas pushing down crust into the mantle followed by plates colliding into each other and pushing oceanic crust down to the mantel, many different styles coexisted, just as they do today.

"Understanding how tectonics worked early in Earth history is key for identifying when and how we got the styles of modern tectonics we see today, and how these styles might be expected to look early in planetary development for other possibly habitable planets," Mixon said.