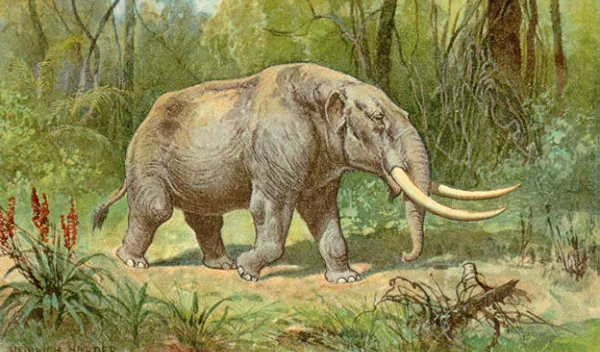

Mastodon tusk chemical analysis reveals first evidence of one extinct animal's annual migration

Around 13,200 years ago, a roving male mastodon died in a bloody mating season battle with a rival in what is now northeast Indiana, nearly 100 miles from his home territory, according to the first study to document the annual migration of an individual animal from an extinct species.

The 8-ton adult, known as the Buesching mastodon, was killed when an opponent punctured the right side of his skull with a tusk tip, a mortal wound that was revealed to researchers when the animal's remains were recovered from a peat farm near Fort Wayne.

Northeast Indiana was likely a preferred summer mating ground for this solitary rambler, who made the trek annually during the last three years of his life, venturing north from his cold-season home, according to a paper in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The U.S. National Science Foundation-supported study also shows that the Buesching bull may have spent time exploring central and southern Michigan. "For the first time, we've been able to document the annual overland migration of an individual from an extinct species," said University of Cincinnati paleoecologist Joshua Miller, the study's first author. "Using new modeling techniques and a powerful geochemical toolkit, we've been able to show that large male mastodons like Buesching migrated every year to the mating grounds."

University of Michigan paleontologist and study co-leader Daniel Fisher participated in the Buesching mastodon excavation. He later used a bandsaw to cut a thin, lengthwise slab from the center of the animal's banana-shaped, 9.5-foot right tusk, which is longer and more completely preserved than the left.

That slab was used for the new isotopic and life-history analyses, which enabled scientists to reconstruct changing patterns of landscape use during two key periods: adolescence and the final years of adulthood. The Buesching mastodon died in a battle over access to mates at age 34, according to the researchers.

"You've got a whole life spread out before you in that tusk," said Fisher, who has studied mastodons and mammoths for more than 40 years and helped excavate dozens of the extinct elephant relatives. "The growth and development of the animal, as well as its history of changing land use and changing behavior -- that history is captured and recorded in the structure and composition of the tusk."

The team's analyses revealed that the Buesching mastodon's original home range was likely in central Indiana. Like modern-day elephants, the young male stayed close to home until he separated from the female-led herd as an adolescent.

As a lone adult, Buesching traveled farther and more frequently, often covering nearly 20 miles per month, according to the researchers. His landscape use varied with the seasons, including a dramatic northward expansion into a summer-only region that included parts of northeastern Indiana -- the presumed mating grounds.

Under harsh Pleistocene climates, migration and other forms of seasonally patterned landscape use were likely critical for the reproductive success of mastodons and other large mammals.