Meet a colorful but colorblind spider

Jumping spiders, the flamboyant dandies of the eight-legged set, have names inspired by peacocks, cardinals and other colorful icons.

But University of Cincinnati scientist Nathan Morehouse and an international team of researchers found that one jumping spider might have little appreciation for its own vivid splendor. The research was funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation.

"Gaining a better understanding of the mechanisms of color perception in non-human animals can provide information on human color perception issues like color blindness, and help us develop better mechanisms to improve color perception and ultraviolet light detection," said Jodie Jawor, a program director in NSF's Division of Integrative Organismal Systems.

Morehouse examined Saitis barbipes, a common jumping spider found in Europe and North Africa. Males have a furry red crown and legs. Their color seems to complement their elaborate courtship dances to woo discerning females.

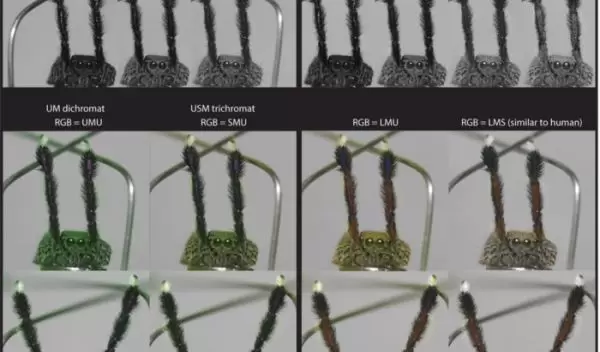

Biologists collected spiders for lab study and used microspectrophotometry at the University of Cincinnati to identify photoreceptors sensitive to various light wavelengths or colors. Unexpectedly, they found no evidence of a red photoreceptor. Likewise, they looked for colored filters within the eye that might shift green sensitivity to red but found none.

Instead, they identified patches on the spider that strongly absorb ultraviolet wavelengths to appear as bright "spider green" to other jumping spiders. The red colors that are so vivid to us likely appear no different than black markings to jumping spiders.

The study was published in the journal The Science of Nature.

Animals use color in all sorts of ways, including camouflage, warning potential predators of their toxicity, showing off to potential mates or intimidating rivals. But it's not always apparent what bright colors might signify, Morehouse said.

The research, according to Morehouse, is a reminder of how animals can sometimes perceive the world in ways far different than us. For example, sunscreen absorbs ultraviolet light extremely well, but we never notice because we can't see that spectrum.

Morehouse is director of the University of Cincinnati's Institute for Research in Sensing, which examines the way we and other animals perceive the world. For example, "what does a wind turbine or a car window or a high-rise look like to a bird that might run into it?" he asked. "We need to consider their perceptual worlds to coexist."