Network Telescope Offers Global View of Internet's Dark Side

Something weird is happening in Romania. That was only one of the surprises that researchers with the Cooperative Association for Internet Data Analysis (CAIDA) found when they began analyzing data from UCSD's network telescope -- one of only a handful of such instruments that provide a global view of the dark side of the Internet.

Unlike many network monitoring tools, UCSD's network telescope looks at the literal dark side of the Internet -- Internet traffic destined for an unoccupied section of the Internet, with legal addresses but no active computers. By monitoring this supposedly dark section of Internet, the CAIDA team has shed new light on denial-of-service attacks and Internet worm infestations.

"The telescope provides us with a unique window on activities that shouldn't be happening," said David Moore, senior technical manager for CAIDA, which is based at the San Diego Supercomputer Center at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD). "The telescope gives us a view of what's going on and what might be coming up, as well as clues for how to build better defense systems."

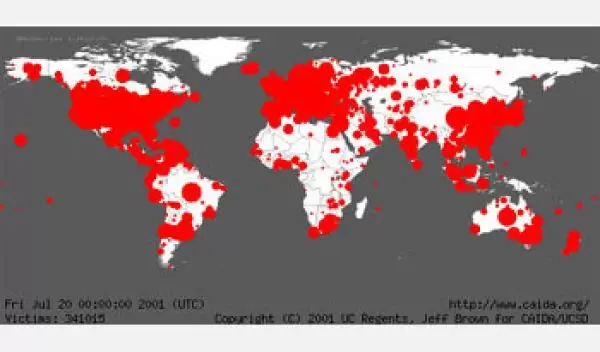

In July 2001, for example, the network telescope captured a picture of the Internet buckling under the spread of the Code Red worm, which infected nearly 360,000 computers in less than 14 hours. Then in a mere 10 minutes in January 2003, the Sapphire (or Slammer) worm infected at least 75,000 computers -- an estimated 90 percent of the computers vulnerable to that worm. Then in March 2004, the Witty worm infected 12,000 computers all running the same software, from an Internet security company no less.

"Each of these worms pushed the envelope in a different way," Moore said. "Code Red was a wake-up call, that these things could happen so fast. Slammer came along and did the same thing in 10 minutes.

"Witty infected a smaller number of hosts, but it still worked. It showed that niche products are not necessarily immune. Witty is also the first destructive worm to succeed. It shows an attack sophisticated enough to keep a machine up long enough to spread before killing it."

Among the lessons learned from CAIDA's analysis of the telescope data is "the extent to which home and small office users have on Internet health," said CAIDA researcher Colleen Shannon. "These are the biggest pool of systems that make the attacks possible."

A second lesson is that the patching model for fixing security problems just isn't working, according to Shannon. Even though vendors had released patches to eliminate the vulnerabilities exploited by each of the three worms, thousands of computers were still infected.

While the telescope has shed light on Internet worms, that wasn't the primary reason it was established. The idea came almost by accident, Moore said. As part of their ongoing Internet analysis, CAIDA had set up monitors to watch traffic on parts of the Internet. And they soon noticed a lot of what they imagined was junk data -- messages destined for vacant Internet addresses.

(Some of the traffic picked up by the telescope is, in fact, junk -- caused by broken software, errors or typos. Understanding this "background noise" is important for developers of security tools who need to distinguish true junk from malicious behavior.)

Closer analysis revealed that much of the so-called junk was actually the fall-out from denial-of-service (DoS) attacks, in which an Internet server is overloaded with phony requests for information. Because the phony requests often forge a random return address, the victim sends some responses into the unoccupied section of Internet monitored by the network telescope.

By analyzing these misguided responses, CAIDA researchers and their UCSD collaborators painted an eye-opening picture of DoS attacks on the Internet. Their results confounded the expectations of security experts.

"There's a continuous background level of attacks," Shannon said. "People didn't know the attacks were going on continuously. There are people who use them as a personal tool to get revenge, or even to slow down game performance."

While the network telescope can see high-profile attacks, such as the controversial December 2003 attack on the SCO Group, Inc. that CAIDA analysis indicates was genuine, most denial-of-service attacks are short attacks on low-profile sites.

For example, computers in Romania, according to CAIDA's analysis, had an extremely high attack rate relative to the Internet infrastructure in that country; the attack rate landed Romania in the top 10 countries in number of attacks. While Romania has a low overall volume of Internet traffic, the country is a notorious hotbed for hackers. While there's no way to know for sure, Moore suspects that Romanian hackers may use the attacks for personal vendettas.

Besides worms and DoS attacks, the telescope can also see scanning activity -- automated tools methodically testing Internet addresses to find systems with vulnerabilities or previously installed back doors.

Further analysis of telescope data—currently one terabyte per month is being collected—might reveal other clues to how the dark side works. For example, the telescope might show whether a new attack is targeting a specific system or is the result of some global activity, which would allow system administrators to respond appropriately.

The network telescope is also part of an NSF cybersecurity research center. The Center for Internet Epidemiology and Defenses at UCSD and the International Computer Science Institute in Berkeley, Calif., is dedicated to wiping out the Internet worms and viruses that infect thousands upon thousands of computers and cause billions of dollars in down time, network congestion and potentially lost data.

"You really have to know how things behave out there" to defeat these epidemics, Moore said of the telescope's role in the center. The center is working to understand how the Internet's open communications and software vulnerabilities permit worms to propagate. The research team wants to use this information to devise a global-scale early warning system to detect epidemics in their early stages, to develop forensics capabilities for analyzing wide-ranging infections and to develop ways to suppress outbreaks before they reach pandemic proportions.

-- David Hart