In new view, Earth's mantle looks like a painting

In grade-school science textbooks, Earth's mantle is usually shown in a yellow-to-orange gradient, a nebulously defined layer between the crust and the core.

To geologists, the mantle is much more than that. It's a region somewhere between the cold crust and the bright heat of the core. It's where ocean floor is born and where tectonic plates die.

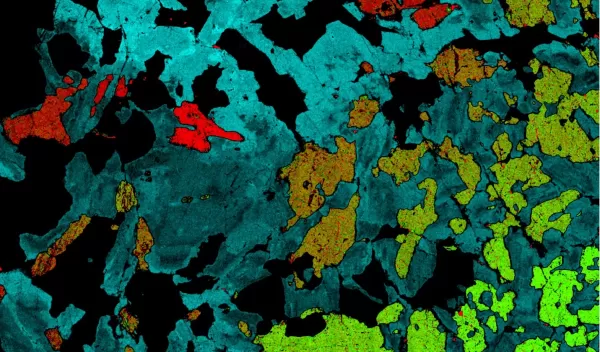

A new paper published in Nature Geoscience paints a more intricate picture of the mantle as a geochemically diverse mosaic, far different than the relatively uniform lava that eventually reaches the surface.

The study was led by Sarah Lambart, a geologist at the University of Utah, and was funded by NSF's Division of Earth Sciences. Lambart visualizes the mantle as connected reservoirs, like dots and lines on a canvas.

"If you look at a painting by Jackson Pollock, you see a lot of different colors," Lambart says. "Those colors represent different mantle components, and the lines are magmas produced by the components and transported to the surface."

Scientists' best access to the mantle comes in the form of lava that erupts at mid-ocean ridges. These ridges run along the ocean floor, where they generate new ocean crust.

Lambart and her colleagues wanted to find out what the mantle looks like before it erupts in lava at a mid-ocean ridge. They examined cores drilled through ocean crust to see the first minerals to crystallize.

The geoscientists found that different rocks melt at different temperatures. Some create channels that transport magma to the crust. Networks of channels then converge toward the mid-ocean ridge but don't mix -- like the streaks of paint on a Jackson Pollock painting. As a result of the findings, the researchers have developed a new view of Earth's mantle.