One is bad enough: Climate change raises the threat of back-to-back hurricanes

Getting hit with one hurricane is bad enough, but a U.S. National Science Foundation-supported study by Princeton University researchers shows that back-to-back versions may become common for many areas in coming decades.

Driven by a combination of rising sea levels and climate change, destructive hurricanes and tropical storms could become far more likely to hit coastal areas in quick succession, the researchers found. In a study published in the journal Nature Climate Change, the investigators said that in some areas, like the Gulf Coast, such double hits could occur as frequently as once every three years.

"Rising sea levels and climate change make sequential damaging hurricanes more likely as the century progresses," said Dazhi Xi, the study's lead author. "Today’s extremely rare events will become far more frequent."

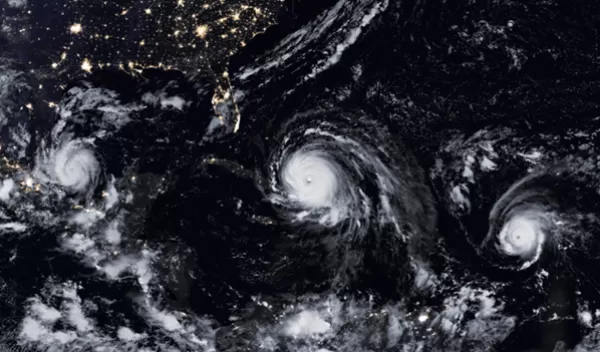

Researchers led by Ning Lin at Princeton first raised questions about increasing frequency of sequential hurricanes after a particularly destructive hurricane season in 2017. That summer, Hurricane Harvey struck Houston, followed by Irma in South Florida and Maria in Puerto Rico.

The emergency planning challenges raised by three major hurricanes led researchers to question whether multiple destructive storms could occur more readily due to climate change, and what steps could be taken to prepare. In the late summer of 2021, Hurricane Ida struck Louisiana, followed shortly by Tropical Storm Nicholas, which made landfall as a hurricane in Texas.

The researchers said their study showed that sequential storms have become more common on the East and Gulf coasts, although they remain relatively rare. "Sequential hurricane hazards are happening already, so we felt they should be studied," Lin said. "There has been an increasing trend in recent decades."

The researchers ran computer simulations to determine the change in likelihood of multiple destructive storms hitting the same area within a short period of time, such as 15 days over this century. They looked at two scenarios: A future with moderate carbon emissions and one with higher emissions. In both cases, the chance of sequential, damaging storms increased dramatically.

"The proportion of storms that can have an impact on communities is increasing," Lin said. "The frequency of storms is not as important as the increasing number of storms that can become hazardous."