Parasitic worms have armies, produce more soldiers when needed

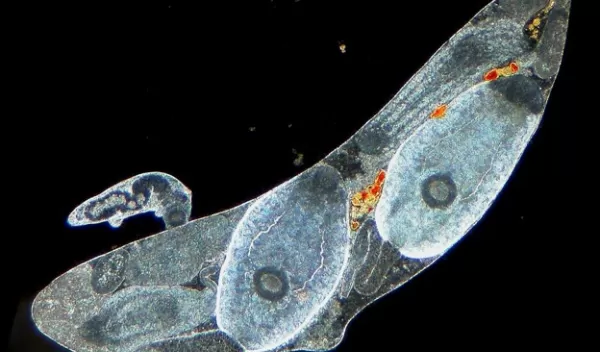

In estuaries around the world, tiny trematode worms take over the bodies of aquatic snails. These parasitic flatworms invade the snails’ bodies and use them to support the worm colony, sometimes for more than a decade, "driving them around like cars," according to Ryan Hechinger, a scientist at California's Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

Like many other highly organized animal societies, including bees and ants, trematode colonies form castes to split the workload. Some trematodes, called reproductives, are larger and do all the reproduction for the colony, while smaller worms with larger mouths, known as soldiers, protect against outside invasion from competing trematodes.

In a new study published in Biology Letters, the research team demonstrated that the number of soldiers in a trematode colony depends on the local invasion threat, showing that such societies produce greater standing armies in areas of greater threat. The results have implications for understanding how animal societies determine their resource allocation.

"Each trematode colony is built of clones from a single invading worm," said Hechinger. "They don't want to share their snail with another trematode, so as their population takes over their host, they start producing soldiers to fight off any potential invaders."

But the real question was whether the trematodes produced more soldier worms when they lived in environments where they were more likely to encounter invaders.

To find out, the researchers collected snails at 38 sites from 12 estuaries with varying invasion threat levels along the North American Pacific coast and brought them back to the lab for analysis.

Snails collected in locations where there was a high risk of being invaded by other parasites had larger numbers of soldier worms poised to attack a new threat.

The sampling effort, funded by the National Science Foundation, included counting trematode worms from six separate species. All but one showed the same pattern of more soldiers in response to higher risk, indicating that this trait is generalizable among trematode species, families and even orders, providing support that this may be true for other animal societies.

"Trematodes are the cause of several serious human diseases," said Sam Scheiner, a program director in NSF's Division of Environmental Biology. "Understanding their biology is critical for disease control."