Researchers engineer tiny, shape-changing machines that deliver medicine to the GI tract

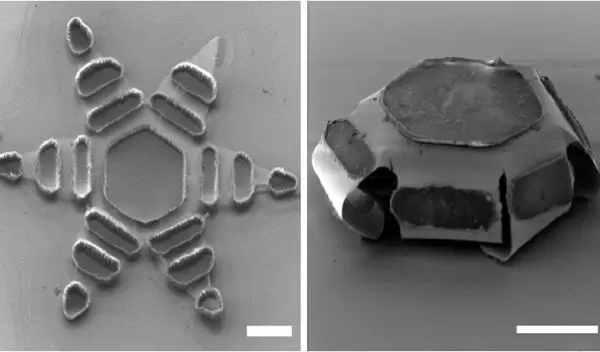

Inspired by a parasitic worm that digs its sharp teeth into its host's intestines, Johns Hopkins University researchers have designed tiny, star-shaped microdevices that latch onto intestinal mucosa and release drugs into the body.

Made of metal and thin, shape-changing film and coated in a heat-sensitive paraffin wax, "theragrippers," each roughly the size of a dust speck, can carry a drug and release it gradually into the body.

The team published its results as the cover article in the journal Science Advances. The research was funded by the Scalable Nanomanufacturing Program of the U.S. National Science Foundation.

Gradual or extended release of a drug is a long-sought goal in medicine. A challenge with extended-release drugs, however, is that they often make their way through the gastrointestinal tract before they've finished dispensing their medication.

Thousands of theragrippers can be deployed in the GI tract. When the paraffin wax coating on the grippers reaches the temperature inside the body, the devices close autonomously and clamp onto the intestinal wall. The closing action causes the tiny, six-pointed devices to remain attached, then they release their medicine payloads gradually into the body.

Khershed Cooper, a program director in NSF's Directorate for Engineering, credits a 3D NISE (3D Nanomanufacturing by Imprint and Strain Engineering) method developed by the researchers in the manufacture of the theragrippers. The method combines patterning thin films and manipulating their properties at the nanoscale.