Scientists explore dinosaur 'coliseum' in Denali National Park

Scientists at the University of Alaska Fairbanks have discovered and documented the largest known single dinosaur track in Alaska. The site, located in Denali National Park and Preserve, has been dubbed "The Coliseum" by researchers.

The Coliseum is the size of one-and-a-half football fields and contains layer upon layer of prints preserved in rock. The site is a record of multiple species of dinosaurs over many generations that thrived in what is now Interior Alaska nearly 70 million years ago. The U.S. National Science Foundation-supported scientists describe the site in the journal Historical Biology.

"It's not just one level of rock with tracks on it," said Dustin Stewart, the paper's lead author. "It is a sequence through time. Until now, Denali had other track sites, but nothing of this magnitude."

At first glance, the site is unremarkable in the context of the park's vast landscape — a layered, rocky outcrop rising 20-plus stories from its base.

"When our colleagues first visited the site, they saw a dinosaur trackway at the base of this massive cliff," said Pat Druckenmiller, senior author of the paper and director of the University of Alaska Museum of the North.

Stewart recalled being initially underwhelmed when he approached the site at the end of a 7-hour hike. Then dusk approached, and the team took another look. "When the sun angles itself perfectly with those beds, they just blow up," Stewart said. "Immediately all of us were just flabbergasted, and then Pat said, 'Get your camera.' We were freaking out."

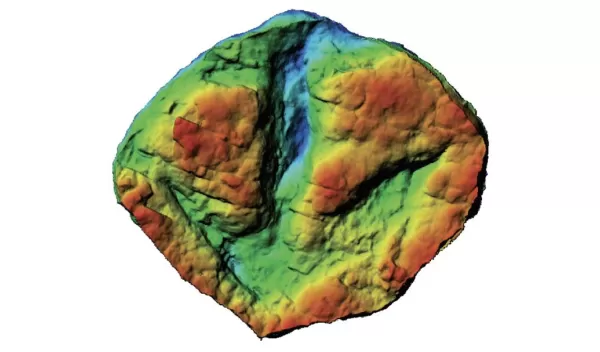

In the late Cretaceous Period, the cliffs that make up The Coliseum were sediment on flat ground near what was likely a watering hole on a large flood plain. As Earth's tectonic plates collided and buckled to form the Alaska Range, the formerly flat ground folded and tilted vertically, exposing the cliffs covered with tracks.

The tracks are a mix of hardened impressions in the ancient mud and casts of tracks created when sediment filled the tracks and then hardened.

"They are beautiful," Druckenmiller said. "You can see the shape of the toes and the texture of the skin." In addition to the dinosaur tracks, the research team found fossilized plants, pollen grains, and evidence of freshwater shellfish and invertebrates.

Based on the tracks, a variety of juvenile to adult dinosaurs frequented the area over thousands of years. Most common were large plant-eating duck-billed and horned dinosaurs. The team also documented rarer carnivores, including raptors and tyrannosaurs, as well as small wading birds.

"These findings are significant because tracks can be informative of diversity and behavior," said Alberto Perez-Huerta, a program director in NSF's Division of Earth Sciences. "Researchers can also use them to reconstruct the environment in which dinosaurs lived."