Scientists take cues from Jules Verne to study life at the 'center of the Earth'

In a modern-day journey to the center of the Earth, scientists are exploring the depths of the Soudan Underground Mine in Minnesota's Vermilion Range.

There the researchers are working to understand the interaction of microorganisms and rocks thousands of feet down. The mine is the state's oldest and deepest iron mine.

In the late 19th century, prospectors in the region found veins of hematite laden with more than 65 percent iron. An open pit mine soon opened, then moved underground in 1900. Mining was active until operations ceased in 1962.

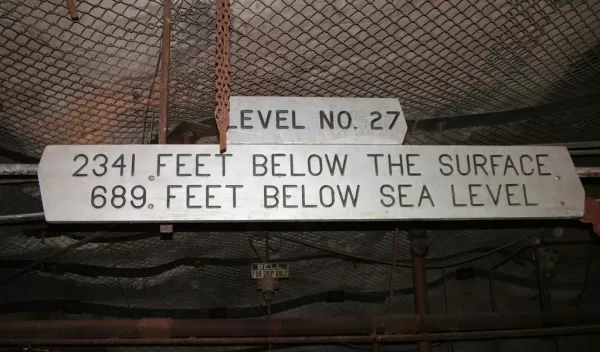

When the mine closed, it reached 2,341 feet below the surface. The miners employed an unusual technique: they dug into the cavern's ceiling, then used the waste rock to raise the floor by the same amount the ceiling had been excavated. The ceiling and floor, therefore, were kept at a constant - and narrow - 10 to 20 feet apart.

That's the environment National Science Foundation (NSF) grantees Brandy Toner of the University of Minnesota and colleagues are delving into. They're studying microbes that thrive deep in the Soudan Mine. The microbes make their living from the mine's iron-rich rock.

"The results are important to understanding how microbial life affects energy extraction processes such as fracking, and underground waste disposal, including spent nuclear materials," says Toner.

The researchers call the interaction between microorganisms and deep rocks the life-Earth connection.

"These rocks were originally extracted because they're so rich in iron -- also the reason the microbes 'eat' them," says Dennis Geist, a program director in NSF's Division of Earth Sciences, which funded the research. "This abandoned mine is a unique natural laboratory for studying the microbes that make up a significant portion of life on Earth: the subsurface biosphere."