Seismologists peer into Earth's inner core

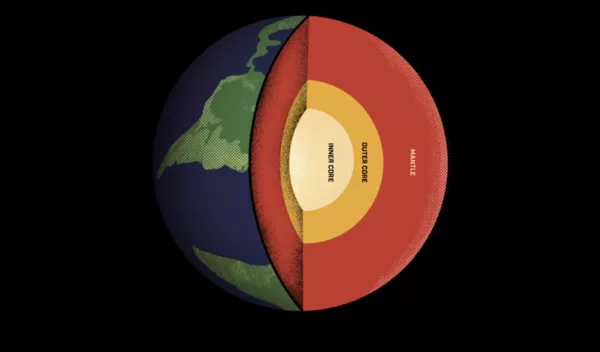

At the center the Earth is a solid metal ball, a kind of "planet within a planet," whose existence makes life on the surface possible.

How Earth's inner core formed, grew and evolved over time remains a mystery, one that U.S. National Science Foundation-supported University of Utah-led researchers are seeking to plumb with the help of seismic waves from naturally occurring earthquakes. While this 2,442-kilometer-diameter sphere comprises less than 1% of the Earth's total volume, its existence is responsible for the planet's magnetic field, without which Earth would be a much different place.

"This project's innovative repurposing of data collected from nuclear test monitoring gives us a more complete picture of the Earth's inner core and its complexity"

- Eva Zanzerkia

But the inner core is not the homogenous mass that was once assumed by scientists, but rather it's more like a tapestry of different "fabric," according to Guanning Pang, a researcher at Cornell University.

"For the first time we confirmed that this kind of inhomogeneity is everywhere inside the inner core," Pang said. Pang is the lead author of a new study published in Nature that opens a window into the deepest reaches of Earth.

"What our study was about was trying to look inside the inner core," said University of Utah seismologist Keith Koper, who oversaw the study. "It's a frontier area. Anytime you want to image the interior of something, you must strip away the shallow effects. So, this is the hardest place to make images, the deepest part, and there are still things that are unknown about it."

This research harnessed a special dataset generated by a global network of seismic arrays set up to detect nuclear blasts. In 1996, the United Nations established the Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization to ensure compliance with the international treaty that bans such explosions.

Its centerpiece is the International Monitoring System, featuring four systems for detecting explosions using advanced sensing instruments sited all over the world. While their purpose is to enforce an international ban on nuclear detonations, they have yielded data scientists can use to shed new light on what's going on in Earth's interior, oceans and atmosphere.

These data have facilitated research that illuminated meteor blasts, identified a colony of pygmy blue whales, advanced weather prediction and provided insights into how icebergs form.

"This project's innovative repurposing of data collected from nuclear test monitoring gives us a more complete picture of the Earth's inner core and its complexity," said Eva Zanzerkia, a program director in NSF's Division of Earth Sciences. "Though challenging to image, the structure of the inner core is important for understanding the Earth's magnetic field as well how the Earth and other planets formed."

While Earth's surface has been thoroughly mapped and characterized, its interior is much harder to study since it cannot be directly accessed. The best tools for sensing this hidden realm are earthquakes' seismic waves propagating from the planet's thin crust and vibrating through its rocky mantle and metallic core.

"The planet formed from asteroids that were sort of accreting," Koper said. "They're running into each other and generating a lot of energy. The whole planet, when it’s forming up, is melting. The iron is heavier and you get what we call core formation. The metals sink to the middle, and the liquid rock is outside, and then it essentially freezes over time. The reason all the metals are down there is because they're heavier than the rocks."

Earth's core, which measures about 4,300 miles across, is comprised mostly of iron and some nickel, along with a few other elements. The outer core remains liquid, enveloping the solid inner core.

"It's like a planet within a planet that has its own rotation and it's decoupled by this big ocean of molten iron," said Koper.