Utah's red rock metronome

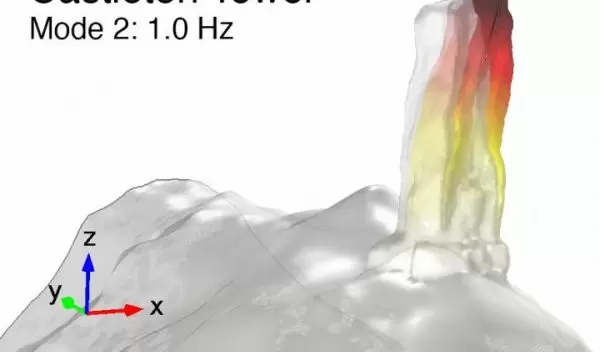

At about the same rate your heart beats, a Utah rock formation called Castleton Tower gently vibrates, keeping time and keeping watch over the sandstone desert below. Swaying like a skyscraper, the red rock tower taps into deep vibrations in the earth -- wind, waves and far-off earthquakes.

New research by University of Utah geologists details the natural vibrations of the tower, measured with the help of two skilled rock climbers. Understanding how this and other natural rock forms vibrate, they say, helps us keep an eye (or ear) on their structural health and helps us understand how human-made vibrations affect seemingly unmovable rocks. The results are published in the Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America.

Castleton Tower is a spire of Wingate Sandstone nearly 400 feet tall that stands over Utah's Castle Valley. First climbed in 1961, Castleton is one of the largest freestanding rock towers.

"Most people are in awe of its stability, in its dramatic freestanding nature perched at the end of a ridge overlooking Castle Valley," says geologist Jeff Moore, who led the study. "It has a stoic power in its appearance."

Moore and his colleagues study the vibrations of rock structures, including arches and bridges, to understand what natural forces act on these structures. They also measure the rocks' resonance, or the way the structures amplify the energy that passes through them.

The scientists have refined their methods as they've surveyed arches, bridges and hoodoos, which are small spire-like formations -- towers on a smaller scale. Hear Castleton Tower here.

"Communicating science using 'sound art' is opening the field to new ears," says Justin Lawrence, a program director in NSF's Division of Earth Sciences, which funded the research. "This unique approach will ultimately broaden participation in geology."