'Zapping' untreated water gets rid of more waterborne viruses

Using sophisticated microscopy and computational analysis, Texas A&M University researchers have validated a water purification technology that uses electricity to remove and inactivate waterborne viruses. The water purification strategy could add another level of safety against pathogens that cause gastrointestinal ailments and other infections in humans.

"There is always a need for new techniques that are better, cheaper and more effective at safeguarding the public against disease-causing microorganisms," said Shankar Chellam, an engineer at Texas A&M University. "The water purification technique investigated in this study is a promising strategy to kill even more viruses at the earliest stages of water purification."

The U.S. National Science Foundation-funded researchers detailed their findings in the journal Environmental Science & Technology.

“Electrocoagulation is a promising alternative to conventional chemical-based coagulation approaches,” said Christina Payne, a program director in NSF’s Directorate for Engineering. “Through its single-step pathogen coagulation and inactivation process, minimizing the need for chemical production and transportation, electrocoagulation may reduce the environmental impact and energy demands of wastewater treatment plants.”

Before water reaches homes, it undergoes multiple purification steps including coagulation, sedimentation, filtration and disinfection. Conventional coagulation methods use chemicals to trigger the clumping of particles and microbes in untreated water. These aggregates can then be removed when they settle as sediments. While effective, Chellam noted that the chemicals used for coagulation are very acidic, making their transport to treatment plants and their storage a challenge.

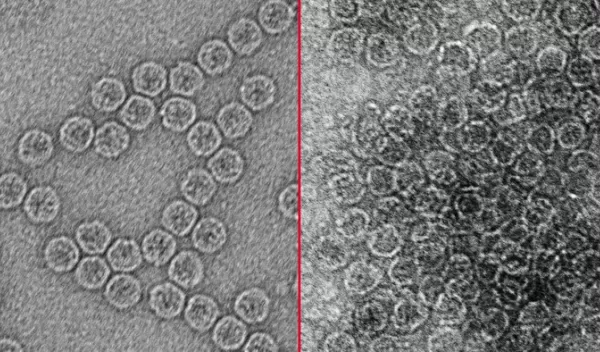

Instead of chemical-based coagulation, the researchers investigated whether a coagulation method that uses electricity is as effective at removing microbes from water. They used a surrogate of a nonenveloped virus, called MS2 bacteriophage. Their choice of microbes was motivated by the fact that MS2 bacteriophage shares structural similarities with many nonenveloped viruses that can persist in water after treatment and cause disease in humans.

"The traditional multistep process of water purification has been there to ensure that even if one step fails, the subsequent ones can bail you out -- a multiple barrier approach, so to speak," Chellam said. "What we are proposing with electrocoagulation is process intensification, where coagulation and disinfection are combined in a single step before subsequent purification stages, to ensure better protection against waterborne pathogens."