Engineers studying how PFAS interact with environment

Improved understanding is first step toward remediation

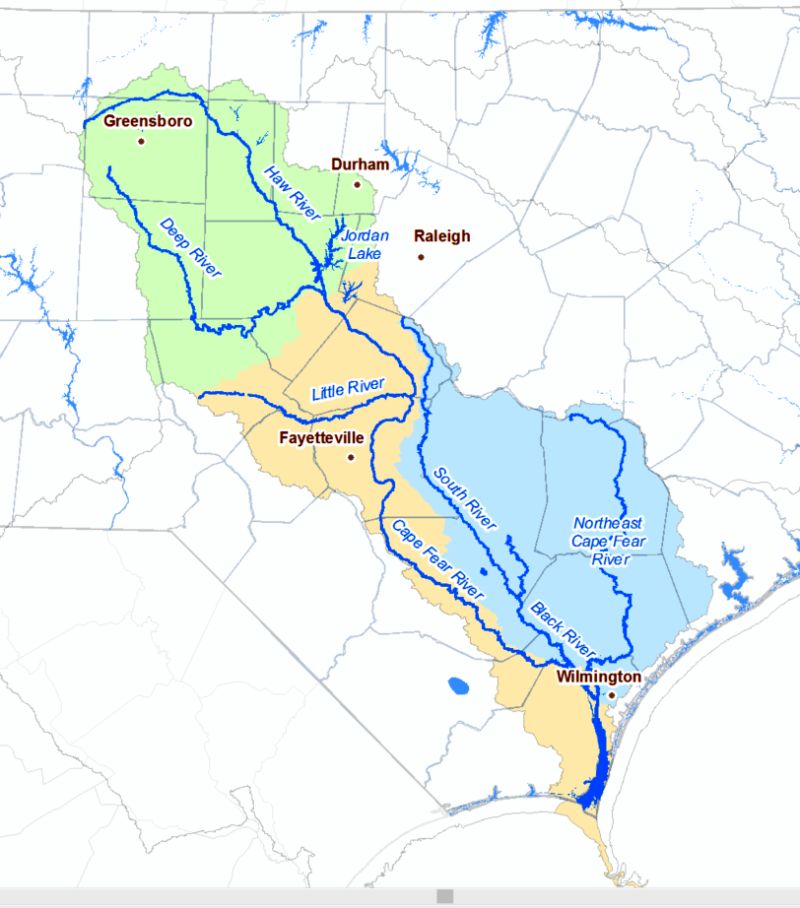

Environmental engineer Detlef Knappe was surveying water quality in North Carolina watersheds in 2013 when his team found something surprising in the Cape Fear River Basin: high levels of a group of human-created chemicals called “PFAS” that are linked to a host of health issues, including cancer.

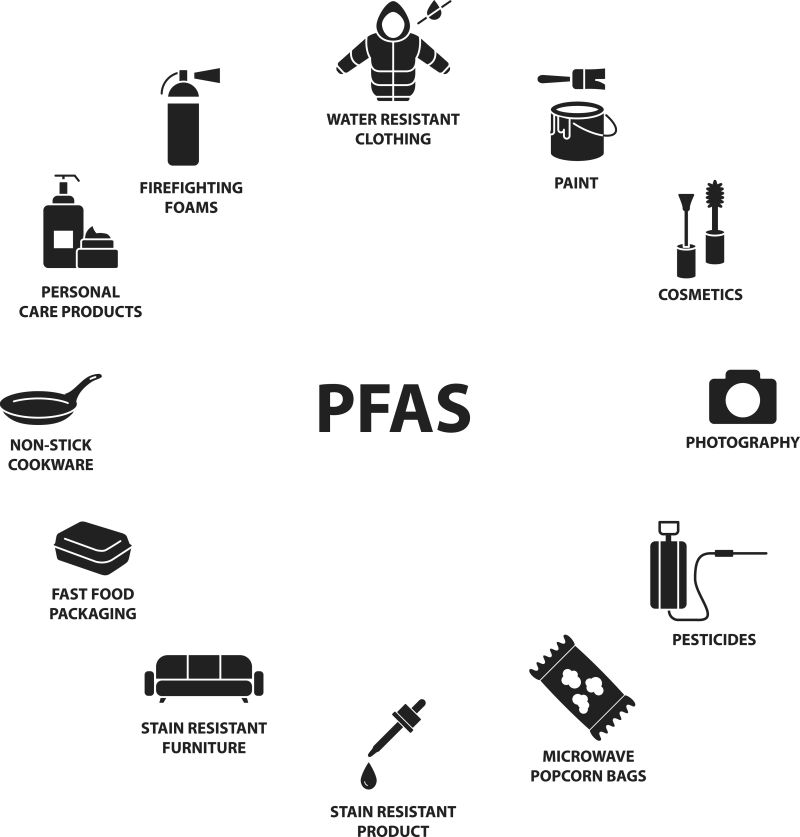

PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are a class of chemical compounds that show high chemical stability due to the strong bonds between carbon and fluorine. They have been used worldwide since the 1940s to make a wide range of consumer products, including food packaging, personal care products, nonstick cookware, stain-resistant fabrics and paint. Airports, industrial sites and military installations also contribute to higher PFAS levels in water, soil and air.

The high stability of these chemicals makes them resistant to processes that normally break chemicals down in the environment, which is why they are called “forever chemicals.” They persist and can build up in a person’s bloodstream and organs — by some estimates, everyone in the U.S. has PFAS in their blood.

Research suggests that long-term exposure to high levels of some PFAS can have a range of health impacts. In 2002, the U.S. began phasing out production and use of some PFAS, but thousands of others remain in production, and new ones are still being developed. Even phased-out PFAS can still be found in the environment, and in food and drinking water.

Tracking PFAS in North Carolina

Knappe, a professor at North Carolina State University in Raleigh, and his students, with support from two NSF grants, spent several years investigating PFAS chemicals, including GenX, found in the Cape Fear River Basin, which is used as a drinking water source for up to 1.5 million people in North Carolina. The team wanted to better understand where the chemicals were originating and where the contamination was spreading. Their findings sparked a movement to clean up the Cape Fear River watershed.

“There was a very immediate outcry from public officials and community members,” Knappe said. The N.C. Department of Environmental Quality ordered The Chemours Company, a chemical company spun off from DuPont in 2015, to stop discharging into the river and collect their processed wastewater. As a result, PFAS and GenX levels downstream of the plant have decreased. The state is now monitoring for PFAS and has set goals to limit the amount of chemicals found in drinking water.

Knappe counts NSF’s investments as a big success. “While they were rather small monetarily,” he said, “they were probably the most impactful grants I had in terms of making a difference for the public.”

Reducing contamination from PFAS

“The persistence of PFAs in the environment is the challenge,” said Jeanne VanBriesen, division director of NSF’s Division of Chemical, Bioengineering, Environmental and Transport Systems. “It's one of a class of chemicals that are famous because of how they remain in the environment a long time. Natural processes that would degrade or break down other chemicals don’t work on these. Understanding the fundamental questions of where these chemicals go and what controls their movement can give us insights on effective ways to remove it from our drinking water.”

PFAS are largely impervious to today’s conventional water treatment methods. In the last few years, NSF research has explored development of new filtration systems, including an ongoing material science project involving Knappe to see if a combination of environmentally friendly graphene oxide and cyclodextrin can selectively capture PFAS. The study will contribute to the fundamental understanding of the molecular interactions of PFAS and provide information for the development of sustainable strategies for PFAS remediation.

In 2021, NSF invested more than $4.1 million in nine fundamental research projects to create new strategies to remove PFAS from the environment. Researchers are using a range of approaches, from capturing the chemicals to changing them into benign products. This research is co-funded by NSF’s Environmental Engineering program in the Division of Chemical, Bioengineering, Environmental and Transport Systems, and DuPont de Nemours Inc.

“This research investigates how to remove PFAS from water and soil, and how to transform PFAS into chemicals that can be broken down in the environment,” VanBriesen said. “The new remediation methods must be feasible, effective and sustainable.

“What we learn with PFAS may be extended to other chemicals – ones we know about today, and ones we don't know about yet. The new techniques and deeper understanding of these chemicals in the environment should help us in the future.”