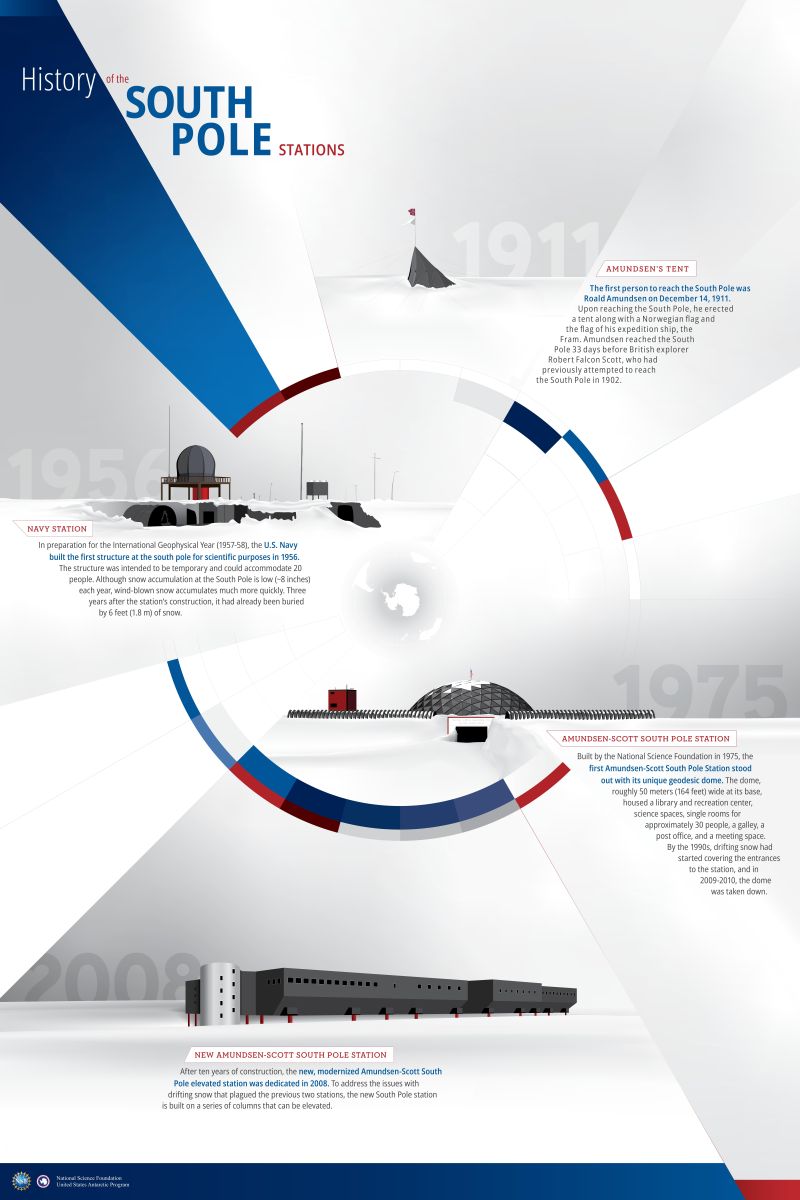

How human presence at South Pole has evolved over the past century

The geographic South Pole sits more than 800 miles from the nearest coastline of Antarctica. It's one of the most remote and harsh environments on the planet, sitting atop an ice sheet nearly 2 miles thick. The Pole is a lonely place — only accessible by plane for about three months out of the year, yet it's one of the best places to conduct astrophysics and atmospheric research. It's currently home to some of the U.S. National Science Foundation's most sophisticated research facilities, with two telescopes to study the cosmos and the world's largest neutrino detector.

For Antarctica Day, which recognizes the anniversary of the signing of the Antarctic Treaty in 1959, here's a look at the history of human infrastructure at the South Pole and how the human presence there has grown since explorers first reached the Pole in 1911.

Amundsen's tent (1911)

The first humans to reach the South Pole were Roald Amundsen and his team of Norwegian explorers on December 14, 1911. After a two-month journey south from the Antarctic coastline, Amundsen's team erected a tent at the Pole and named their camp Polheim, flying the Norwegian flag and the flag of their ship, the Fram. Amundsen's team only stayed at the Pole for four days. A month later, a British party led by explorer Robert Falcon Scott reached the Pole and saw Amundsen's tent, a sign that the Norwegian party had arrived first. Irish explorer Ernest Shackleton made an unsuccessful attempt to reach the Pole in 1914, but humans did not set foot at the South Pole again until 1956.

U.S. Navy Station (1956)

The U.S. Navy built the first structure at the South Pole for scientific purposes in 1956. The station was built in preparation for the International Geophysical Year (1957-1958), a collaborative, worldwide effort to study the Earth and sun like never before.

The station housed 20 scientists and support staff who studied the character of snow and ice at the Pole, observed how the East Antarctic Ice Sheet moved, and recorded air temperatures. Researchers also made observations of auroras, finding that geomagnetic storms and auroras at the South Pole were mirrored at the North Pole at the same time.

The Navy station marked the start of the continuous presence by the U.S. at the South Pole. The original station was never intended to be a permanent structure. Wind-blown snow began to cover the station after several years, so plans were made to build a more enduring structure. A new station was completed in 1975, but the original Navy structure remained until it was deconstructed in 2010.

Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station (1975)

The first permanent structure at the South Pole was built in 1975 and named Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station, after the first two explorers to reach the Pole. The station was commissioned by NSF and built by the U.S. Navy construction battalion, also known as the Seabees.

The station had a unique geodesic dome 164 feet wide at its base to protect it from the elements. The station housed a library and recreation center, science laboratories, single rooms for approximately 30 people, a galley, a post office and a meeting space. In the 1990s, astrophysics and atmospheric research at the Pole took off, with several large telescopes built during this time to observe the cosmos. The Pole soon became one of the world's premier locations for conducting microwave astronomy, which scientists use to study the origins of the universe.

Just as with the Navy station, drifting snow had started covering entrances to the station by the 1990s, and plans began to build a new station in its place.

New Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station (2008)

In 1997, construction began on a new building to replace the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station. To address the issues with drifting snow that had plagued the previous two stations, the new station was designed as an airfoil and built on a series of columns that can be elevated. The station faces into the wind and its airfoil shape forces air into a compressed space where it accelerates and scours away any built-up snow. In addition, the columns allow the entire station to be lifted up two additional stories to keep it from being buried.

Construction took 10 years and required transporting 24 million pounds of cargo from the United States to Antarctica. More than 900 flights were necessary to move construction materials from McMurdo Station on the Antarctic coast to the South Pole. Due to the harsh weather, crews only had about 100 building days a year to work.

Today, the new Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station can house 150 people and has its own greenhouse and a series of underground tunnels for storage. The station was dedicated in 2008 for the International Polar Year, and the geodesic dome that covered the previous station was taken down in 2010.

The new station allows NSF to conduct world-class astronomy, astrophysics, and atmospheric research that can't be done elsewhere in the world. The station is home to the IceCube Neutrino Observatory, Earth's largest neutrino detector, and an atmospheric research observatory that samples the most pristine air on the planet. In the coming years, researchers plan to expand IceCube's capabilities and install a fiber-optic network of seismic sensors around the Pole that will allow them to study movements of the ice sheet in greater detail.