The Pacific Islands: The front line in the battle against climate change

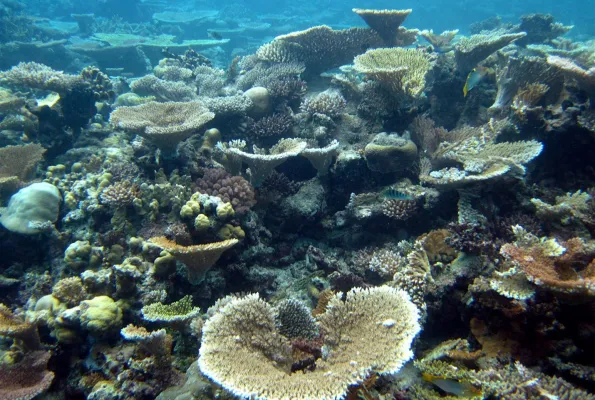

The Pacific Islands have unique, diverse environments and marine ecosystems — reef fish live among coral in crystal blue waters; turtles graze sea grass beds; tangled mangrove roots shelter tiny fish and crabs; coconut trees fringe white sandy beaches; and, in the skies, tropic birds and albatross soar.

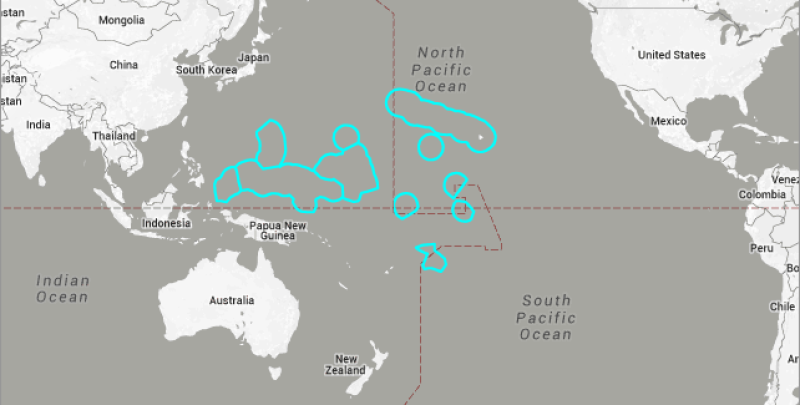

There are over 25,000 Pacific Islands encompassing 15% of the Earth's surface. Although the population is relatively small, with over 2.3 million people and 1.4 million of those residing in U.S.-affiliated islands, the region has over 1,750 unique languages.

The three main cultural groups of the Pacific Islands — Melanesian, Polynesian and Micronesian — have a long history of maritime exploration starting around 1500 B.C. and reliance upon the natural resources of the ocean and coasts for food, clothing and other essential materials, with a culture of traditional storytelling, passing down legends of exploration, and sharing community wisdom. That Indigenous knowledge is now being recognized as important in helping to conserve ocean resources in the face of a changing ocean.

The threat of climate change

The Pacific Islands region is one of the first regions experiencing the impacts of climate change. Many of the islands are low-lying, often atolls or other islands that rise only a few feet above sea level. The current pace of sea level rise has not been seen for 5,000 years and threatens these low-lying island systems with flooding, coastal erosion and storm surges. An average sea level rise of between 25 cm – 58 cm is predicted by the middle of this century along the coastlines of Pacific Island countries, which would be devastating for islands that sit at or just above sea level. If global temperatures increase 2degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels, as is becoming increasingly likely, it is estimated that 90% of the coral reefs in much of the Pacific Island region could suffer severe degradation, which will have a devastating effect on the marine species that depend upon these ecosystems.

Researchers at the University of Hawai'i at Mānoa, Haunani Kane and Charles Fletcher, have integrated fossil data, historical photographs and modern observations of extreme tide and wave events to estimate when these island systems may become unstable. They found that under a variety of climate change scenarios, every island system they studied would be threatened during the 21st century. In the most likely climate change scenario, the rate of sea level rise would triple, groundwater sources will be permanently lost in the next few decades, with islands becoming unstable in the second half of this century. Under a more negative climate change scenario, the sea level would rise by a meter, rendering the islands unstable in the next 20 to 40 years and exposing many human communities to intolerable levels of risk by the year 2060.

Climate change is affecting fisheries and many threatened marine species. Over the coming decades, climate change impacts are expected to become more widespread and severe.

The small island states of the Pacific are only responsible for 0.03% of global greenhouse gas emissions, but they are disproportionally facing many of the threats of climate change head on.

Sparking STEM interest in the region

Despite these threats, environmental biology and ocean sciences have not traditionally been considered viable career options by many Pacific Island peoples, and historically there has been little local scientific capacity.

The Partnership for Advanced Marine and Environmental Science Training for Pacific Islanders is trying to change that. The NSF-funded program has helped to enhance marine and environmental science education at the five minority-serving community colleges of the Pacific Islands: American Samoa Community College, the College of Micronesia-FSM, the College of the Marshall Islands, Northern Marianas College and Palau Community College. The program has developed educational curricula, from secondary school through college level, and the program has also aided the professional development of secondary school teachers and community college faculty by providing research and field experiences as well as essential scientific equipment for schools.

This long-term program is seeing some amazing successes with students who became enthused as high school students and who are now teachers and college professors, helping to teach the newest cohort of students.

"NSF-ATE program has been foundational and extremely impactful in advancing highly relevant STEM training for one of the most highly underrepresented minorities in these fields — Pacific Islanders," said Robert Richmond, one of the organizers of the program and a professor at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. To date, more than 3,500 Pacific Island students have directly benefited, with around 70% continuing with additional training following completion of their degrees at the regional community colleges, including graduate training. "The program is building a critical regional capacity of culturally connected scientists who are performing cutting-edge research, outreach and education to their home communities and serving as role models for the future generations of Pacific Island scientists, technicians, policymakers and leaders,” Richmond said.

Alexi Meltel, a graduate student at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, is an alumna of the program currently conducting research on protein and gene expression in corals in Palau.

"I benefited greatly from my experience," said Meltel. "Not only was I being exposed to marine science, but I was learning alongside people who were from the same backgrounds and mindsets as well. Having a cohort of fellow Pacific Islanders to learn with strengthened my confidence in my own research project and encouraged me to make the most of my experience. We could relate well with each other which made us all very comfortable and more open to learning."

The experience has had a major influence on the course of Meltel's life. "I fell in love with marine invertebrates and their importance to Pacific Island cultures and ecosystems. From then on, I decided that I wanted to be a marine biologist who studied corals in the Pacific."

"Conducting my research in Palau is important to me because I can contribute to the knowledge about Palau's corals." That knowledge could help in the race against a changing climate. “Being able to do my research about my home island is also very gratifying for me because I feel like I'm doing my part to protect Palau's oceans for future generations," Meltel said.

The Pacific Islands are at the front line of climate change impacts, and this program is providing Pacific Islanders with the scientific skills and resources to enable local communities to tackle the effects of climate change to help protect their islands, coastal waters and marine resources, and their way of life.