Breaking up is hard to do: Separation of Fiji and Vanuatu tied to Samoan seamounts

The islands of Fiji and Vanuatu rise from the tropical waters of the South Pacific in one of the most tectonically active and geologically complex regions of the world. A U.S. National Science Foundation-supported study of volcanism in this area sheds light on the ancient breakup of a long island arc, which swung apart like "double saloon doors."

Fiji and Vanuatu started out as close neighbors and ended up 800 miles apart on separate sections of what had once been a continuous arc.

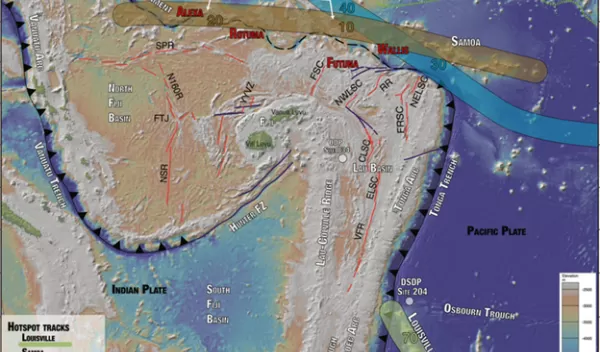

Island arcs form where a plate of the oceanic crust sinks beneath an adjacent plate in a process known as subduction, giving rise to a belt of volcanoes parallel to the trench where the descending plate bends downward. The islands are the tallest peaks of vast underwater mountain ranges built up by volcanic activity in the subduction zone. One such range now goes from New Zealand up to Tonga, then bends westward to Fiji. Another extends from New Guinea down to Vanuatu.

"They all used to be connected to one another, and then they got split apart in the geologic past," explained James Gill at University of California, Santa Cruz, and first author of a paper in Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. "This paper attributes the breakup to the subduction of the Samoan Seamount Chain."

Samoa, like Hawaii, is part of a linear chain of volcanic seamounts formed as the oceanic crust moves over a "hotspot" in the Earth's mantle, causing a series of volcanoes to grow over that spot. A long chain of seamounts extends to the west of the Samoan islands.

"When that chain of seamounts got pushed down into the earth underneath the island arc, it caused indigestion in the subduction zone, which ultimately broke it apart," Gill said.

In addition to the seamounts getting hung up in the subduction zone, other complex processes were at work across the island arc, including a reversal of the direction of subduction along part of the arc, the rotation of different segments, and the opening of rifts where seafloor spreading creates new oceanic crust. The Vanuatu arc rotated clockwise while the fragment of crust bearing Fiji rotated counterclockwise.

These events, dubbed "double-saloon-door tectonics," began about 10 million years ago and proceeded slowly over millions of years, leading up to the present configuration of the islands. The Samoan seamounts are the best match for the rocks that erupted in Fiji at the time this island arc broke apart, the scientists found.

"This study elegantly solves the complicated tectonic history of Vanuatu and Fiji," said Gail Christeson, a program director in NSF's Division of Ocean Sciences.