Finding Cures from Corals

Surrounded by countless predators, many of the ocean's sedentary animals rely upon powerful toxins for defense. NSF-funded researcher William Fenical and his colleagues have shown that in addition to defeating hungry sea creatures, these potent chemicals can actually help humans defeat disease.

Fenical is director of the Scripps Center for Marine Biotechnology and Biomedicine at the Institute of Oceanography in La Jolla, California. "For over 25 years," says Fenical, "NSF has supported our studies to define the roles of chemical compounds in the adaptations of marine organisms within a competitive environment."

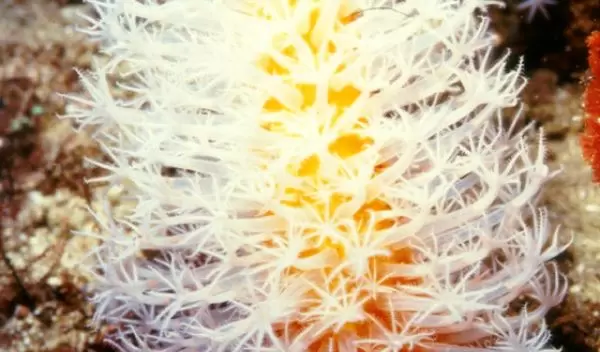

One of the team's early NSF-supported discoveries was pseudopterosin, an anti-inflammatory chemical found in the Caribbean sea-whip Pseudopterogoria elisabethae. Sea-whips are feathery corals that can grow several meters high, but only centimeters wide. Like most corals, Pseudopterogoria are actually colonies of thousands of soft, anemone-like animals only a few millimeters across.

In a triumph of successful wildlife management, Fenical and his colleagues devised a method of harvesting the branched colonies of these tiny animals in a manner akin to collecting plants.

"Who would ever have thought you could harvest a coral reef? Instead of collecting an animal by pulling it off of its habitat," says Fenical, "you chop it like pruning a bush – then it grows back in an entirely robust way." In total, feathermen (named after the "sea feathers" they collect) can harvest 3-4000 kilograms of coral in a season with no harm to the ecosystem.

According to Fenical, in 18 months the sea-whip population is not only restored, it is healthier than before harvesting began. The coral has become a sustainable, long-term resource, selling for around $35 per pound. The impoverished feathermen can hunt coral instead of the other threatened and endangered organisms in the Bahamian ecosystem – a relationship that has the strong backing of both the Bahamian government and ecologists who come to study the program and its success.

Because pseudopterosin has the ability to defeat allergic responses in the skin, it has been successfully marketed by Estée Lauder for the last seven years. In addition, pseudopterosin has been licensed to a small pharmaceutical firm for medical use as an anti-inflammatory drug to treat such conditions as contact dermatitis. The compound is among the University of California’s top ten royalty-producing inventions.

Another of Fenical's success stories is a potential treatment for cancer. In 1993, while diving off the coast of Australia in the shallow bay called Bennett's Shoal, Fenical discovered a small, yellow coral now called Eleutherobia. Two years later, Thomas Lindel -- then Fenical's post-doctoral student and now a faculty member at Germany's University of Heidelberg -- extracted the chemical eleutherobin from the coral.

Researchers found that eleutherobin behaves similarly to the anti-cancer drug taxol -- both chemicals bind to cellular microtubules, preventing cancer cell division. Eleutherobin may prove to have advantages over taxol, perhaps causing fewer of the side effects -- including immune system suppression, nausea, and hair loss.

Fenical and his colleagues are now studying the myriad bacteria and fungi that live in the sea, and the potentially revolutionary chemicals that the microorganisms produce. Says Fenical, "Like the discovery of penicillin in 1929 which showed that microbes are a fantastic source of drugs .... the microbes in the oceans have an even greater promise.... I view this area, marine microbiology, as the most important new source for pharmaceuticals on the planet."

However, Fenical asserts that our understanding of marine microorganisms is in a nascent stage. "We need to learn more about them," he says, "learn to culture them well, and understand their roles in the marine environment before we can fully exploit this major resource."

Already, he and his colleagues have identified two new compounds that are being developed for cancer treatments and one antiviral compound that may help patients with Herpes simplex.

The National Science Foundation has long recognized the importance of William Fenical's research. He received his first substantial grant in 1975 from the Division of Ocean Sciences within the Directorate for Geosciences. Through the years, his work has also been supported by the Directorate for Mathematics and Physical Sciences' Division of Chemistry and by the Office of International Science and Engineering. Fenical's research is also supported by the National Institutes of Health.

-- Andrea Spiker