Gene variations for immune and metabolic conditions have persisted in humans for more than 700,000 years

Like a merchant of old, balancing the weights of two commodities on a scale, nature can keep different genetic traits in balance as a species evolves over millions of years.

These traits can be beneficial (for example, fending off disease) or harmful (making humans more susceptible to illness), depending on the environment.

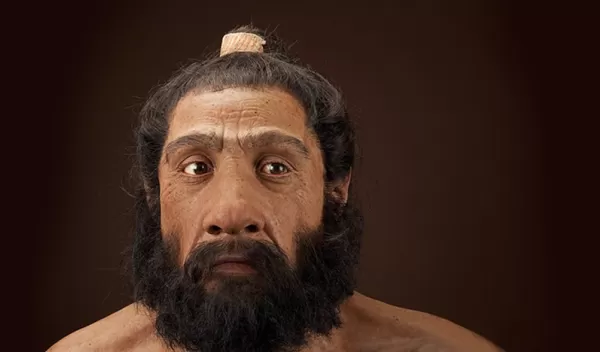

The theory behind these evolutionary trade-offs is called balancing selection. A University at Buffalo-led study published in eLife explores this phenomenon by analyzing thousands of modern human genomes alongside those of ancient hominin groups, such as Neanderthals and Denisovans.

The U.S. National Science Foundation-supported research has "implications for understanding human diversity, the origin of diseases and biological trade-offs that may have shaped our evolution," says evolutionary biologist Omer Gokcumen, the study's corresponding author.

Gokcumen adds the study shows that many biologically relevant variants have existed "among our ancestors for hundreds of thousands, or even millions, of years. These ancient variations are our shared legacy as a species."

The work builds upon genetic discoveries in the past decade, including when scientists uncovered that modern humans and Neanderthals interbred as early humans moved out of Africa.

It also coincides with the growth of personalized genetic testing, with many people now claiming that a small percentage of their genome comes from Neanderthals. But humans have more in common with Neanderthals than those small percentages indicate.

Some genetic variations can also be traced back to a common ancestor of Neanderthals and humans that lived about 700,000 years ago. The research team explored this ancient genetic legacy, focusing on a particular type of genetic variation: deletions.

Gokcumen says that the "deletions are strange because they affect large segments. Some of us are missing large chunks of our genome. These deletions should have negative effects and, as a result, be eliminated from the population by natural selection. However, we observed that some deletions are older than modern humans, dating back millions of years ago."

The investigators found that deletions dating back millions of years are more likely to play an outsized role in metabolic and autoimmune conditions but may also have been an advantage in the context of disease or starvation.

Rebecca Ferrell, NSF Biological Anthropology program director, says that "the project demonstrates the value of an expanding genomic toolkit for studying human evolution, revealing new details about the complex variation and relationships among hominins."