Genomic study reveals signs of tuberculosis adaptation in ancient Andeans

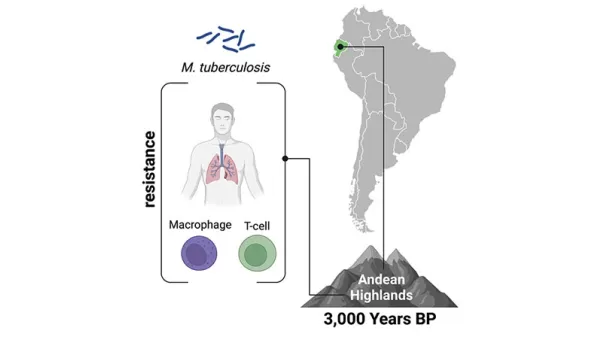

People have inhabited the Andes mountains of South America for more than 9,000 years, adapting to the scarce oxygen available at high altitudes, along with cold temperatures and intense ultraviolet radiation. A new genomic study published in the journal iScience suggests that indigenous populations in present-day Ecuador also adapted to the tuberculosis bacterium, thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans.

The study, led by scientists at Emory University, was supported through multiple U.S. National Science Foundation grants.

"We found that selection for genes involved in TB-response pathways started to uptick a little over 3,000 years ago," says Sophie Joseph, first author of the paper. "That's an interesting time because it was when agriculture began proliferating in the region. The development of agriculture leads to more densely populated societies that are better at spreading a respiratory pathogen like TB."

The investigators had originally set out to investigate how the Indigenous people of Ecuador adapted to living at high altitude.

"We were surprised to find that the strongest genetic signals of positive selection were not associated with high altitude but for the immune response to tuberculosis," says John Lindo, senior author of the study. "Our results bring up more questions regarding the prevalence of tuberculosis in the Andes prior to European contact."

Previously published research found evidence of the tuberculosis bacterium in the skeletal material of 1,400-year-old Andean mummies, contradicting some theories that TB did not exist in South America until the arrival of Europeans 500 years ago.

The current paper provides the first evidence for a human immune-system response to TB in ancient Andeans and gives clues to when and how their genomes may have adapted to that exposure.

"Human-pathogen co-evolution is an understudied area that has a huge bearing on modern-day public health," Joseph says. "Understanding how pathogens and humans have been linked and affecting each other over time may give insights into novel treatments for any number of infectious diseases."

The researchers sequenced whole genomes using blood samples from 15 present-day Indigenous individuals living at altitudes above 2,500 meters in several different Ecuadorian provinces. They performed a series of scans to look for signatures of positive selection for genes in their ancestral past.

"Computational techniques for sequencing genomes and modeling ancestral selection keep improving," Joseph says. "The genomes of people living today give us a window into the past."