How the Pacific's marine heat wave came back

Weakened wind patterns likely spurred the wave of extreme ocean heat that swept the North Pacific last summer, according to new research funded by the National Science Foundation and led by the University of Colorado Boulder and the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

The study was conducted at NSF's California Current Ecosystem Long-Term Ecological Research site.

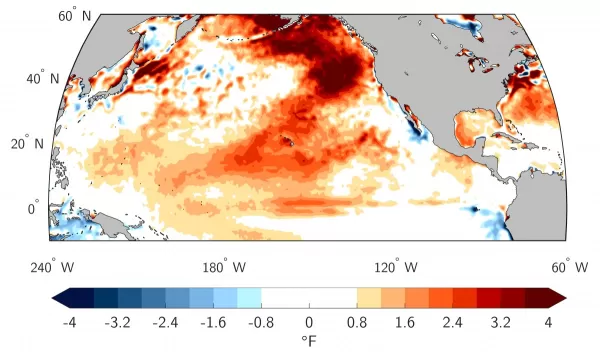

The marine heat wave, named the "Blob 2.0" -- after 2013's "the blob," a large mass of relatively warm water in the Pacific -- likely damaged marine ecosystems and hurt coastal fisheries. Waters off the U.S. West Coast were a record-breaking 4.5 degrees F (2.5 degrees C) above normal.

"Most large marine heat waves have historically occurred in the winter," said Dillon Amaya, a researcher at CU Boulder and lead author of the study in Nature Communications. "This was the first summer marine heat wave in the last five years, and it's also the hottest -- a record high ocean temperature for the last 40 years."

That wasn't the only record: 2019 also saw the weakest North Pacific atmospheric circulation patterns in at least the last 40 years. "This was truly a 99th-percentile type of event, with impacts like slow winds felt around the North Pacific," Amaya said.

To search for physical processes that might have influenced the formation of Blob 2.0 in summer, the team paired real-world data on sea surface temperature with an atmospheric model and tested the impacts of various possible drivers.

The most likely culprit: weaker winds. When circulation patterns weaken, so does the wind. With less wind blowing over the ocean's surface, there's less evaporation and less cooling. The process is similar to wind cooling human skin by evaporating sweat. In 2019, it was as if the ocean was stuck outside on a hot summer day with no wind to cool it down.

"We can only understand these ecosystem changes if we have sustained, long-term studies like this one of the oceans and atmosphere," says Mike Sieracki, director of NSF's Biological Oceanography Program.

Adds Baris Uz, director of NSF's Physical Oceanography Program, "Upper ocean conditions have always been variable, but a background of gradual warming now makes the ecological and weather impacts of extreme events more acutely felt."