Microbes far beneath the seafloor rely on carbon recycling to survive

Scientists at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution have revealed how microorganisms survive in rocks nestled thousands of feet beneath the ocean floor in the lower oceanic crust. The study is published in the journal Nature.

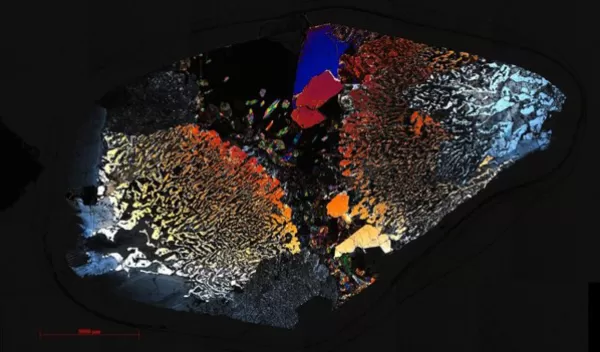

The first analysis of messenger RNA -- active genetic material containing instructions for making proteins -- from this remote region of the Earth, coupled with measurements of enzyme activities, microscopy, cultures and biomarker analyses, provides evidence of a diverse community of microbes that obtain their carbon from both living and dead organisms.

To find out what microbes live at these extremes and what they do to survive, National Science Foundation-funded researchers collected rock samples from the lower oceanic crust during three months aboard International Ocean Discovery Program Expedition 360.

The research vessel JOIDES Resolution traveled to an underwater ridge called Atlantis Bank, which cuts across the Southern Indian Ocean. There, tectonic activity exposes the lower oceanic crust at the seafloor, "providing convenient access to an otherwise largely inaccessible realm," write the co-authors.

"We applied a completely new cocktail of methods to explore these samples as intensively as we could," says Virginia Edgcomb, a microbiologist at Woods Hole, the lead PI of the project and a co-author of the paper. "All together, the data start to paint a story."

Some microbes appeared to have the ability to store carbon in their cells, so they can stockpile for times of shortage. Others had indications that they could process nitrogen and sulfur to generate energy, produce Vitamin E and B12, recycle amino acids, and pluck carbon from hard-to-break down compounds called polyaromatic hydrocarbons.

This rare view of life in Earth's far reaches extends our view of carbon cycling beneath the seafloor, Edgcomb says. "If you look at the volume of the deep biosphere, including the lower oceanic crust, even at a very slow metabolic rate, it could equate to significant amounts of carbon."