Modern Technology Reveals Ancient Footpaths Buried in 2,500 Years Worth of Volcanic Ash

More than 20 years ago, volcano scientists Payson Sheets and Tom Sever teamed up to solve a mystery. While flying over the active Arenal volcano in the mountains of Costa Rica, infrared imaging technology on board their research plane picked up a steady trail--one with a beginning and an ending--concealed deep within the earth. The trail showed a clear path away from what Sheets and Sever knew to be ancient villages in Arenal's foothills. Then, the trail just disappeared.

One of the most active volcanoes in the world, Arenal is located near the city of La Fortuna, about 93 miles northwest of San Jose, and rises above Arenal Lake.The volcano last erupted in 1968, killing 78 people, after it had been dormant for 400 years. The tracks Sheets and Sever saw had been covered by more than 2,500 years of volcanic ash and erosion.

Sheets, an anthropologist at the University of Colorado, wanted to learn more about the villagers who had inhabited the area 2,000 years ago and why had they traversed the trail so vigorously. Why had the villagers continued to return to their native village time after time, even after at least four devastating Arenal eruptions? What made these people so resilient, so persistent? Could the trail picked up by infrared provide the answers?

With funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF), Sheets and Sever, a NASA archaeologist, collaborated for the next 20 years to learn more about the region, its history and its people.

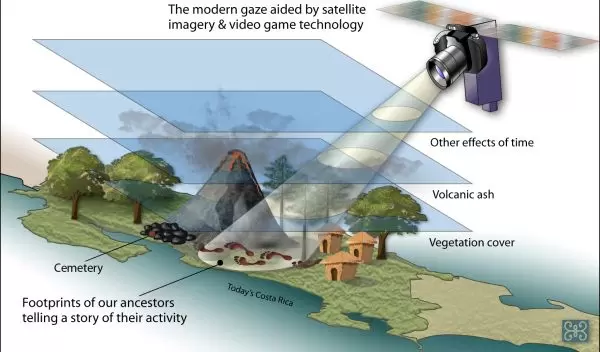

Fast forward to 2004. Sheets and Sever learned that technology used for video games might be useful in digging deeper, virtually, into the past. Using TerraBuilder, provided for free by the company that created it, Sever used 3-Dimensional technology to input layers over the trail and then look through them to discern what they signified and where they went. Without an airplane, Sheets could "fly over" the land using the technology and, without physically disturbing the ground, "unearth" the surroundings and practices of a people long gone. Sheets could see how wide the path was between the residential center and the cemetery, and he could see the extent of erosion over the centuries.

Thanks to the video game technology, work that once took years was plotted in minutes.

Soon, Sheets realized he was looking at the worn footpaths created by ancient villagers between 500 B.C. and 600 A.D. Constant traffic wore the path to a depth between 7 and 13 feet deep. Over time, ancient villagers marched along the path from their homes, creating a tunnel-like trench that became symbolic and sacred. After about 10 miles of single-file walking, the villagers stepped into an open area, which served as the village cemetery. Sheets discovered ancient stones that were used to mark grave sites as well as springs that were used as part of ritual funereal feasts. Before that time, the Arenal people buried their kin simply and without ceremony, alongside family homes.

"When I visited the site in person, it was extraordinary to know that I was following the footsteps of an ancient people, walking on a path that was invisible to the average person in modern times," Sheets said. "The trail wasn’t the easiest path to walk, and the people intended it to be difficult, out of respect for their dead. After a steep incline, I suddenly entered a wide-open area. It was peaceful and serene."

Sheets' and Sever's findings, released in December 2006, reveal much about the changing cultural practices of the peoples in the Arenal region. The scientists were struck by the highly sophisticated way the villagers honored their dead, which, based on their research, was a new concept. Despite the persistent rumblings and explosions of the volcano, the Arenal people treasured their rituals and placed high importance on returning to the land of their forebears where they could reconnect with the dead.

Sheets says the Arenal peoples were more resilient than the Maya and Aztecs. Their diet came from the rich biodiversity of the rainforest and only a small amount from domesticated food. Arenal peoples could survive the devastating volcanic eruptions because they knew how to find food in the wild.

Because of their resilience, Sheets believes the Arenal people returned to the village over the centuries, despite the violent eruptions. "Our earlier analyses of artifacts and architecture could not answer the question of whether the Arenal occupants were the direct descendants of the ones who had to abandon the village. But more recently, when we realized the occupants of the village went right back to their previous practice of using the same path to the same distant cemetery, we became convinced they were the direct descendants," Sheets said. "Now we think the reestablishment of the ritual path to the cemetery, to revere their dead as well as reconnect with the spirits of the deceased, was at least as important as reestablishing the village itself. As the tail wags the dog, so does the trail resettle the village."

NSF's Division of Behavioral and Cognitive Sciences, which funded Sheets' work, supports research to develop and advance scientific knowledge on human cognition, language, social behavior and culture, as well as research on the interactions between human societies and the physical environment.

"'Traditional' societies continue to exist in many parts of the world today," said John Yellen, NSF program director for archaeology and archaeometry. "This groundbreaking research not only provides insight into the past, but it also helps us understand the present."

Sheets plans to use the game technology to also research villages in El Salvador that have been buried deeply in volcanic ash.